Phil: How do we present this to donors? You have to visualize the donors – they’re getting on in years, they aren’t necessarily financially sophisticated, and they’re thinking with their heart as much as with their head. They’re longing to make a difference, and they may not know how. Other people see them as feeble, they see them as having passed it, being over the hill. It’s a lonely, lonely place to be. We’re suggesting they step up to hit their legacy home run with us.

I made this presentation in Dallas. Many of you were there. This photo is of the audience that came. It was a long, thin room, and the advisors are to your left and in the back of the room. But there were almost as many advisors as there were donors. It was a wonderful turnout, it was a wonderful group. I’ll never forget the faces, and how ‘into it’ they were, because I think I was connected with them based on my living some of this myself.

I’m sure that not all of them are still with us. I mean, they are at that age and stage, there were walkers, canes, and wheelchairs in the room – and a wonderful community spirit.

The conversation starts at home. Home is where charity begins, but doesn’t end. Home is where the heart is. Home is where our home-based non-profits are, as an extension of our family. Home is where we say ‘we,’ not ‘them’ and ‘us’. Home is where we say ‘brother’ and ‘sister’ or ‘brethren.’ Home is where we say ‘I vow.’ Home is where at the end, although we’re not there necessarily to hear it, they will say about us or around us, ‘dearly beloved.’

In a somewhat colder Yankee frame of mind is Robert Frost. He said ‘Home is where when you go there, they have to take you in.’ For some people, the only home they have left when their own family is not able to take them in, are the kind of organizations that some of you work with, and support, and have devoted your lives to.

There’s science behind this as well as sentiment. I know it’s true from personal conviction, but science has proven it to be true. Dr. Russell James – the researcher we’ve been relying on – has studies in which he puts legacy-aged donors into MRIs and reads their brains. What he discovered is that when you mention legacy words, two parts of the brain light up. One part is the part that has to do with love and family, and the other part that lights up has to do with what he calls visualized autobiography. Thoughts are triggered about who the person is, who they were, who they are, who they’re becoming, how they visualize their story today, how they visualize the story ending. I will tell you, all of us, each one of us, visualizes our life story as a story about a hero, and that hero is us. I believe that the last heroic thing you can do, really and truly for many of us, is hitting our legacy home run with the help of our advisors and gift planners.

These are conversations which start us at home plate, and by giving this talk directly to the donors, I save you this step. What I’ve found by teaching this now for 13 years is that these conversations need to happen, but nobody is paid enough to do them, nobody has the stamina to do them, nobody can take the time to do them, because they take forever. They go on forever. Insofar as I can put these questions across the donor and client, I can motivate them to go through the rest of the process and save you a step.

These are questions that have become really meaningful to me. This slide is Michael O’Shaughnessy, who teaches ethics in the Bay Area, California. He’s a Jesuit priest and teaches kids in prep school. He heard me give a version of this talk. He said to me,

“‘Phil, I’m the last person to give you advice on how to work with the wealthy. I took a vow of poverty as a Catholic priest, and I’ve kept it; but here are a couple of questions we asked the kids in prep school:

“What kind of person do you want to be? And in what kind of world?”

I can’t think of two better questions for legacy planning than those. What kind of person, what kind of world? It is easy to ask 15-year-olds in the prep school where you’re giving them a grade; but try asking their parents, if their parents are on the board. It takes a lot more brass to ask an older person, ‘What kind of person? What kind of world?’

This slide is Peter Karoff, who had a MFA, Masters in Fine Arts. He founded the Philanthropic Initiative, which is one of the very first philanthropic consulting companies. In that capacity he interviewed very wealthy families about their giving. He wrote them in this book The World We Want. These are his very crafty questions to pull people into the conversation. They’re really business planning kind of questions, like a SWOT (strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats) analysis.

- What is your vision of the world we want, or of a better world, or a better Dallas? (A blue sky, rainbow kind of question.)

- What conditions are needed to realize it?

- What are the obstacles?

- What parts of the vision (this is the planning piece) are realistic?

- What ideas, strategies, and plans can make it so?

- Would you like to work with me on that?

Here’s Tracy Gary, who’s been a mentor to me, as with Peter Karoff. Her book inspired philanthropy.

She helped start Dallas Women’s Foundation. She inherited the equivalent today of $3M as a 21-year-old, and gave it all away by the time she was 30 or 35. Tracy has helped other people do the same. These are among her questions, and I love the way she frames things. These are her words; I’ve tried to preserve her phrasing because she’s so much more eloquent than I am.

- “What would you like to change or preserve in the world (or here in Dallas)?

- Has past giving reflected your hopes?” What does she mean by that? I think she means that, all too often, giving is sterile, frustrating, empty, dry, disappointing. It’s like paying a bill that comes due and that’s all there is to it. ‘It’s on me, here’s another bill to pay.’

- What are the causes behind the issues that move your heart and do you want to address those symptoms or causes?

So, if you’re moved by hungry children, you want to feed them. That’s marvelous, and that’s a really important work to do, feeding them. But, why are there so many? What are the causes behind the issues? What could change the situation?

You’re not going to change the world all by yourself, no matter how rich you are. Who joins you in the work? Your family? Your friends? Your nonprofits? Your initial gifts may not be terribly successful. Just as in business, how will you experiment, learn what works, and revise?

This is Jenny Santi, her book Giving Way to Happiness and she’s got a good question: Who’s your giving tribe? Who do you run with in your giving. Because adults and grown-ups, we don’t do well just doing things by ourselves. We want to socialize what we’re learning with other people.

This is Joe Breiteneicher. I’m now of an age, obviously, where many of the people I learn from are no longer here. I feel – I really, truly feel – an obligation, as well as a privilege, in passing on some of what was alive in the prior generation. It has to live on. This is just too important, a lot of this stuff. Joe was at the forefront of this work. He worked in The Philanthropic Initiative; he took it over after Peter Karoff retired. He had a wonderful sense of humor about giving, which is rare. He died not long after that photo was taken of pancreatic cancer, and he died with that smile on his face, joking with the nurses, as he joked with donors.

He was an interesting guy, and on his shirt you see a Harvard crest. Many of us have been taught – and you know, it makes sense – families should do a mission statement about their money and their giving. Well, it takes forever; it’s somewhat bureaucratic and corporate, and families are not companies. You may have time to do them; Joe didn’t. But, he had a wonderful question. He would say to his donors, ‘If your family had a crest, what would be the motto? Give me two words, just two words, you actually live by – they can be in English, they don’t have to be in Latin – two words you live by.’ I gave this presentation recently to some students who took it home to their kids, and the little kids, six and seven years old, all did a family crest in crayon and they put words into the motto. What a wonderful exercise for a family!

This next slide is Jay Steenhuysen. He’s raised money for Brown. He’s raised money for World Vision. He’s worked for Harris Bank in Silicon Valley, with some really rich families. He has some very wealthy clients who turn to him to guide their philanthropy, and he’s a fundraising consultant. I love this question, I think it will go down really, really well with clients and in Dallas: “Do you recognize, Mr. and Ms. Big, any element of luck, blessing, or grace in your success?”

Some people are going to say with Frank Sinatra, ‘No, no, no. I did it all my way;’ but if they say that, they are probably not good prospects for a significant gift. Most of us, though, recognize that we didn’t do it just by ourselves, and we want to send the elevator back down for the next generation.

This is Tom Tierney. He founded a philanthropic consultant group called Bridgespan that works with extremely wealthy families, hundred-million-dollar type families. Prior to that, he founded a company 20 years ago. He was about 35; he was the co-head of Bain Capital with Mitt Romney. Romney went on to run for president. Tom bailed out and founded this company, Bridgespan, which is a nonprofit, a not for-profit company, it’s a non-profit. He doesn’t have an ownership interest, he’s not making a ton of money. Why did he do it?

I had a chance to interview Tom about his book which is called Give Smart; it’s a great book. He was doing a book tour, and allowed me to interview him. In order to get 15 minutes, I had to go through all kinds of hoops. I had to get all the questions pre-approved by his staff; it was like literally interviewing a president or presidential candidate. He shows up for the interview, I read the questions on the script, he answers them, and he’s getting ready to leave. I say, ‘Tom, there’s another question I’d like to ask you. It’s not on the list,’ and he looks at me, he rocks back in the chair, and has a look on his face as if he is going to say ‘No.’ I said ‘If you don’t want to answer the question, that’s okay, and if you don’t like the answer you give, I promise not to use it’. He said ‘Okay,’ so the question I’d like to ask was, ‘I’m looking at your resume and it was a gold-plated resume when you were 35. You were a king at 35. You could have run for president, like your peer Romney did. Why did you stop that to start a nonprofit when you don’t even have an ownership interest? What motivates you to do it?’ He looked at me, he said, ‘Fair question. I woke up every night asking myself this question: If I’ve only got 10 more years to live, will all this have been enough?’ Many successful people reach that point in life where the answer is ‘No, it will not be enough just to continue to be successful the way I’ve been. I’ve got to make a change.’ Often, that change leads to philanthropy, or giving, or non-profit work.

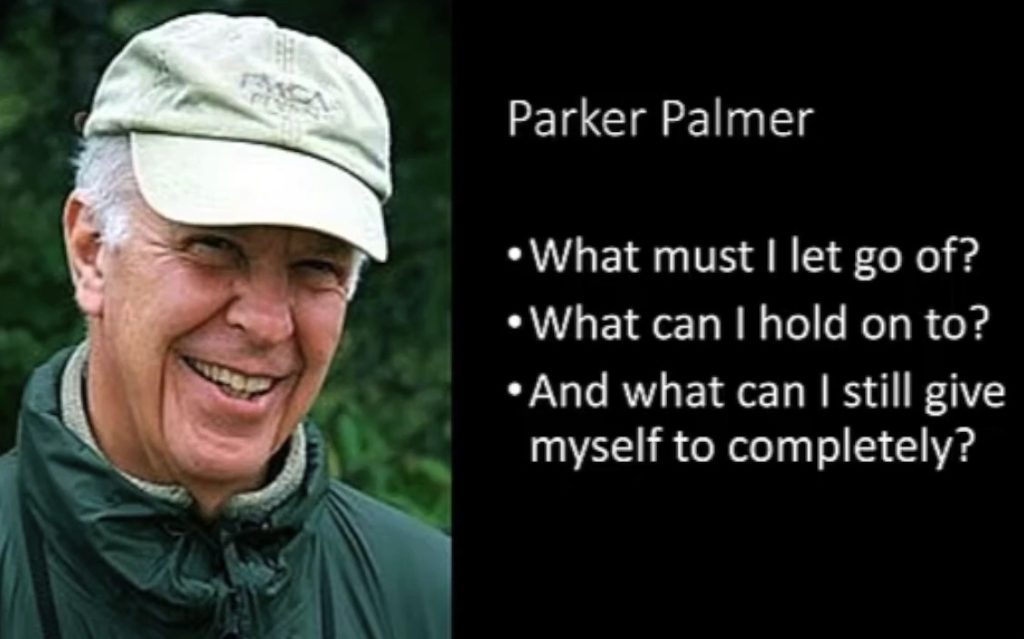

This book made a difference to me and it’s partly why I’m teaching philanthropy now, rather than working for a financial services company. It’s a book by a guy named Parker Palmer and it’s called A Hidden Wholeness. He’s in the Quaker tradition, and he’s written books chronicling his own life stages. He had a midlife crisis, became profoundly depressed, and this was the theme of A Hidden Wholeness: The Journey Toward an Undivided Life. The theme of the book is aligning your soul and your role. Many of us are very successful in life, but we always feel like ‘This wasn’t why I was put on earth. There is more to it than what I’ve done.’

Conversation Starter: Jill, when you were younger, were there things you wanted to accomplish in life that you have not yet done?

Now, for many of us, the answer to that is ‘Yes, very much so,’ and for Jill, she’s of an age where she can – just like Tom Tierney – change direction, and maybe still do it: bail out of her business, sell her business, take the money, do something else. But, as you hit 60, 65, 70, 75, you’re running out of time to do it yourself. But, there’s still a chance to do it through other people. Maybe she’s running a great PR agency, but you want to be a concert pianist. Maybe she can get back to being a concert pianist – I don’t think so – but maybe she can make a gift to let somebody else fulfill her dream symbolically.

This is Charles Collier, “Charlie”. Raised money for Harvard. He was among the very best fundraisers who ever lived. I read a great book called Wealth and Families which you can still get, it’s about $16. These are questions that resonate very much with me as an advisor, somebody trained as an advisor, having worked in an advisory shop doing legacy planning. These are questions that give you pause if you’re an attorney or you’re a CPA or a donor or client.

What principles have guided your legacy plan to date? If I review your documents what are the principles I’ll see in them? I can tell you what they are because I’ve been involved with so many. It’s how the textbooks teach it. The central principles of traditional legacy planning are

- Fear: Fear of losing your money, running out of money, fear of predators and creditors getting your money, etc.

- Greed: Wanting more, always wanting more

- Control: Maintaining control during your life and after your death.

These are really important. Advisors have to do this work with us. It is their stock and trade, their fiduciary responsibility to do those things. We should be grateful they plant us on those principles. But, most of us have more going on than that. We have aspirations of dreams that go beyond that, and we have to drive the process to make sure their higher aspirations are also covered, along with those fundamental principles of having enough for ourselves.

Another really important Charlie question that may well resonate with you: ‘What are you up against with your children? Because, if we’re going to be giving lots and lots and lots of money to your children, will they use it for beneficial purposes or could it end up hurting them?’ A quick story of a person in this tradition of higher order legacy planning today, an advisor, explains how he began to do it. He started as an attorney with very wealthy families. He worked with a family worth $100 million dollars, and he moved all $100 million dollars, tax-free, to the son, who drank himself to death within six months. So what counts as winning in legacy planning is the most possible wealth to the heirs or setting it up so it’s beneficial to them. How wealthy do you want the heirs to be? It’s an open question, it’s a conversation starter.

This is Dien Yuen, who works with me in the CAP Program. She’s a JD and an LL.M. At the time this picture was taken, Dien worked with very wealthy families in the Bay Area, many of them women. She was working very often with the heirs of those families, often women, and she said ‘You’ve got some great questions you might want to add to the deck, here’s what I asked my clients’: Were there things you wanted to do that your father said you couldn’t?

What a question! When I show this slide to audiences, I often get the reaction, ‘Well, yeah, she’s from an Asian culture. They’re very traditional. We’re not like that here in America.’ I’m not so sure. How many of us have been taught that the purpose of a good legacy plan is to pass on your values to your kids? Is that the issue or is the issue helping them to develop their own values? Now, people in this audience will be divided on that point, but this is raising the question, ‘Would you rather pass on your values or help your kids develop their own?’

- These two women founded Vario Philanthropy in St. Louis, and they have some great questions: ‘Do you have any debts of gratitude?’ I know I do, and I’m sure you do.

- ‘What would friends say is your soapbox? What are you on about?’

I can see you’re giving lots of places. We look at your tax returns and we can see charity after charity after charity. You seem to never say no, but where might you sacrifice breadth for depth? Some people call it spray and pray philanthropy, or peanut butter philanthropy, where you spread it too thin. Particularly, for your final gift, your ultimate gift, the gift at the end of life, could you narrow it down to a few, maybe five, maybe three, maybe two, maybe one, where your gift can really make a permanent difference?

Yes, your planning should take care of yourself, your family, your business, and your money. Of course it should, and your advisors are good at doing that, but is there anywhere else in the world you’d like to have a positive impact while you’re alive or after you’re gone. If you ask yourself that and come to an affirmative answer, as I know you will, you’re more likely to discover your documents are somewhat out of date, because you didn’t say that. It’s not the attorney’s fault that you didn’t come to voice it at that moment, but now that you are coming to voice what you’re trying to accomplish, it might be time to go to revisit your documents and make sure that if you do want to have an impact beyond your family, your documents will actually do that.

This slide is of Sharna Goldseker. I believe she’s an heir of the Seagram’s fortune, down many generations now. She works with donors, many of them heirs of the rising generation of Millennials. Her book is called Generation Impact: How Next-Gen Donors Are Revolutionizing Giving. It’s a very good book. Sharna is concerned about the identity of those receiving the inheritance, not just the ones giving it, because she’s an inheritor, she’s a recipient of wealth. She’s asking: ‘What legacy have I inherited from my famous-name family in our community? How do I live into that legacy? How can I be worthy of it? How can I make my own mark in the world where my family has been so famous? How does this legacy that I received inform who I am and how I see the world? How can I take that legacy and carry it forward?

This next slide is Bruce Debofskey. He is an attorney. He ran a non-profit, then went into legal work, and now he’s a full-time philanthropic consultant, a really, really good one. He’s also a syndicated columnist on philanthropy. He says, ‘What we’re working with here is called family philanthropy, and in essence, some families use philanthropy to heal the family. Others use philanthropy to heal the world, and there’s always a balance between those two things.’ I think increasingly today, the times are so hard. Many of our hearts have opened to try to heal the world a little bit better, as well as using philanthropy to heal the family. Sometimes healing the world could be the best path to healing the wounds in the family too.

This is Coventry Edwards-Pitt. She’s written this book Aged, Healthy, Wealthy and Wise. She works in a family office in Boston, and I love her questions for older people – of whom I am one. If you’re listening, and are older too, you can relate to these questions.

- ‘Has your relationship to money changed as you’ve gotten older?’ The answer to that is obviously yes. It used to be all about getting it, now it’s about either keeping it or passing it on, or some of both.

- ‘How have you evolved in how you use your money now that you’re older?’ ‘Evolved’ implies progress, doesn’t it?

- ‘What has been the most rewarding ways in which you have used your wealth now that you’re older?’ I’ll bet it’s not buying things. I’m willing to bet you it is not buying things, unless it’s buying things for the grandkids.

This is Parker Palmer again. Towards the final stage of his life – the time that picture was taken – he was in his early 70s, and he was trying to exit from an organization he started called The Center for Courage and Renewal, a wonderful Quaker-inspired organization teaching people to get back in touch with their deeper motivation, with their ‘inner teacher’ as the Quakers say.

Terribly difficult to give that up. So difficult for many of us to give up our life work as we end the stage life, so hard.

His first two questions he brought into a Quaker circle. The Quaker tradition when you have tormenting questions, you bring the questions to the circle. You speak the questions into the silence of the center of the circle, and in their tradition, the inner teacher speaks from the center of that circle. I think in the Christian tradition, we call it the Holy Spirit. It’s the listening of other people that makes that possible. It’s the quality of that silence that makes it possible.

The first two questions he asked, the ones that he kept circling around and circling around circling around:

- ‘What must I let go of?’

- ‘What can I still hold on to?’ ‘Are you not asking those questions?’ and they were unresolved until the silence of the circle said to him: ‘What can I still give myself to completely, Parker?’

- What can we still give ourselves to completely at this age and stage? It may involve non-profits and giving things that go on after we’re not here.

This is Rabbi Mordechai Liebling. He teaches fundraising. And he teaches the Torah. Speaking as a Rabbi, more than as a fundraiser, here is his question: ‘Your last will and testament is your final teaching. What do you want it to say?’ For those of us who are attorneys, CPAs and financial advisors, this is the level at which the game has to be played, if it’s going to be played successfully.

Those are home base considerations and if they weigh with you, you’re going to want to come home to those at the end of this talk and do something about it. But there’s a path you have to run and it’s really covering all the bases. We know this to be true, and I think the fundraisers notice that the following sections are true, and I think your advisors do, and I think you do too.

Yes, it’s important to leave a legacy, but on first base, after you hit your home run tag first base. First is making sure that there’s enough for you. If I predecease my wife, it’s really important to me that she be able to answer that question affirmatively, that there is enough for her. She’s going to need and want a financial advisor to reassure her of that frequently because even though there may be enough, she may not feel there’s enough. We need financial advice to make sure we have enough, but also to make sure that we take that to heart and feel secure.

This is Ted Turner, a multi-billionaire, who gave away billions. He was interviewed about his philanthropy, and I’ll never forget what he said when they said ‘You’ve done wonderful things. What’s next for you and your giving?’ Ted, he said, ‘What do you want from me? I’m down to my last billion,’ and what that’s saying to me is no matter how much money we have, we often need to be reassured that we have more than we need.

When you make sure you have enough for yourself, you move on to second base which is thinking along Charlie’s lines. How much is enough for the kids? How much is too much? How wealthy do you want to make them? How much is appropriate for your heirs if you have direct heirs? Some do, some don’t. But how much is enough for those who are blood kin, you might say? How much is too much? How much will it help them? How much will it hurt them? Only you can work this out, and it’s a dilemma, and your answer is going to change from day to day, week to week, month to month. It’s going to change as they mature. It’s difficult, but you need to make a decision, and don’t let it stop you from moving forward. You need to make a decision for now, and you can always change your documents later.

This might help you. It’s a worksheet you can get online from a site called thelegacyspectrum.com, but you can also do it just with a single sheet of paper. It’s like a final spending spree. When you’re gone, what do you want your heirs to get? We’re going to add up some numbers: Do you want to buy them a house or just a down payment on a house? Would you like to buy them a vacation house? How big? Do you want to leave an education fund for them and the grandkids? How about a retirement fund so that if they keep contributing, they’ll be able to retire with security? How about a retirement fund so big they retire the day you die? Cars? One car, two cars, three cars? How big of a car? Jewelry? Private clubs?

Most families who do this exercise come to the conclusion that there’s a finite amount: not too much, not too little. The goldilocks amount. In many families listening to this talk, you have more than that number. The right amount is less than you’ve got.

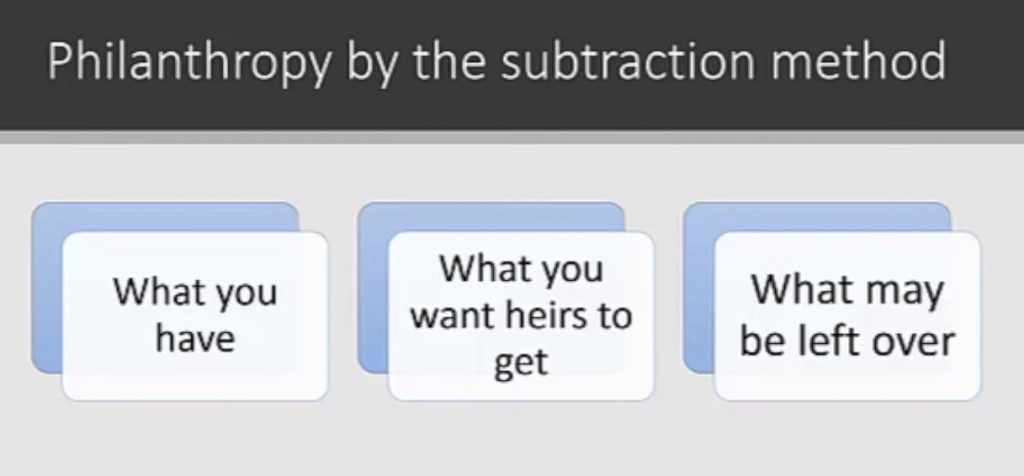

So what is left over? Some people call this “philanthropy by the subtraction method” or “philanthropy for the leftovers.” It’s cold-blooded, but it’s necessary to also be logical. How much do you have, minus how much do you need for yourself, and how much do you want the heirs to get – this nets the amount available to give to philanthropy. That’s after the heirs get their share, what may be left over. This is math. Your advisors do this math every day. This is just math philanthropy by the subtraction method. What do you have, what do you want the heirs to get, what may be left over. A little bit cold-blooded, but it’s good to be logical and your advisors do this every day. They can tell you how much is likely left over, if you can tell them how much you want the heirs to get.

You could call it a “calculation of your ability to be generous,” your charitable capacity. There are various tools that can be used to help you on first base with your income. They can be used to help you on second base with inheritance for the heirs in reducing estate tax, but they’re really designed to also help you get the money back home to home plate.

Now, we’re headed back home. The kinds of things we were talking about when we started, they’re really near and dear to our heart. There is planning needed to go from third base to home base. If you have money that you’re not going to spend, heirs are going to get it. Maybe it’s insurable tools, maybe they come later as a request, but you want to make sure that money is used wisely, and you’re talking to your nonprofit people about making sure it’s going to be used wisely. These are conversations you need to have with them, and they need to have with you at home plate.

My potential gift is big to me. We mentioned Ted Turner in his billions; I haven’t got billions but this gift is big to me. It’s a third of my estate; I worked a lifetime for this money. It’s big to me. Is it big to you? What will we get for that money – and let’s talk about tax deductions. What kind of results? How do we know that this most important gift of a lifetime isn’t going to be wasted?

What impact can we get? What results? What benefit to the community? Will you report back to us about that so that we can be sure? I’m going to give you the money, but somebody’s gotta do the work inside the organization. Can I meet that person? Is the program champion going to do something with my money? The professor, the doctor, the nurse? I’m not all about ego, but can we get some recognition? Could I moralize my mother? Is this done with a handshake, or is there some kind of a gift agreement where we put our understanding in writing?

Most importantly, what good is going to come of it? Will it really matter? Because it matters to me. This is the biggest gift I’ll ever make.

Then, we get to timing. If you’re – as many of you are – on third base, do you want to hit your home run standing up or slide in feet first? When?

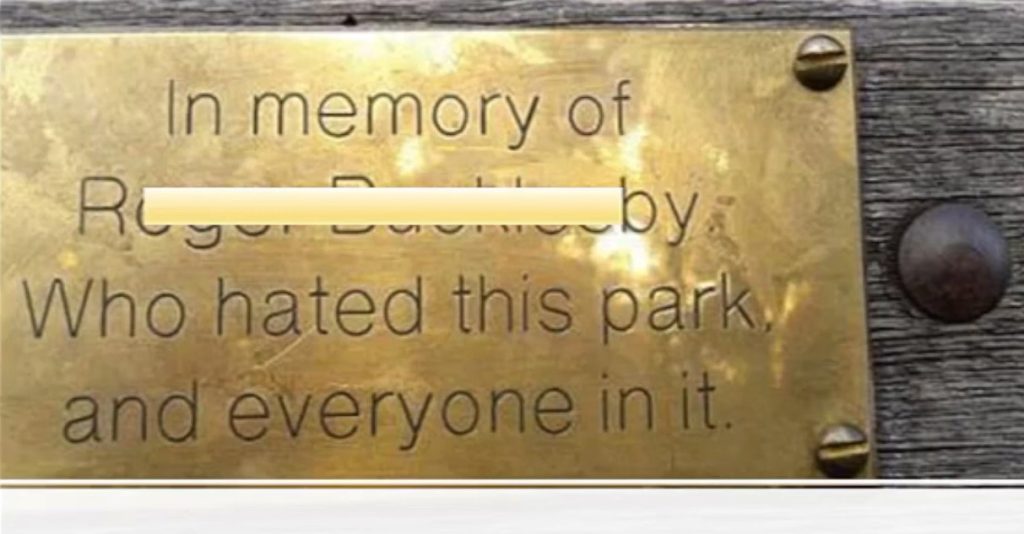

I made this presentation in Dallas in 2018. An attorney and his spouse came up to me afterwards. They saw a wonderful inscription on a park bench in England while on vacation. This was a very old park bench. There was a plaque on there that said ‘Memories fade. Remembrances remain.’ I said, ‘Boy, that’s marvelous. I’ve got to include this in the talk. Thank you.’ So, I went looking on Google to see if I could find that bench. I looked and looked and looked; I didn’t find the bench, but I did find this one: ‘In memory of Roger, who hated this park and everyone in it.”

So, I think the moral here is we’re all going to leave a legacy – one way or the other.

Who is your giving tribe? If your family had a crest, what would be your motto? Is there something else you wanted to do in life but haven’t?

These are only a few of the great questions Phil Cubeta shared during his inspiring presentation, Helping Boomers Hit Their Home Run Legacy. Using a baseball analogy, clients and donors can navigate the “bases” and ultimately create their desired legacy.

People want to pass money and values on to their children at their death. However, charitable organizations need money now. Many have to close their doors because they do not have the funds to maintain the organization. The good thing is, Boomers prefer to give while living, at least a portion of their wealth.

Phil walks us through how donors can give now, and later, and at death.

Philanthropic conversations begin at home, “first base,” where you decide how much is enough for you? It’s important to make sure that there is enough for you. You need to feel secure that you can live on whatever amount you decide upon.

Once that is determined, round to “second base” and decide how much is appropriate for your heirs. How much is too much? Only you can work this out, and your answer will change. The Legacy Spectrum has a great worksheet to aid in this process. Documents can, and should, be updated as situations change.

As you round to “third base,” you see what is left over (what you have minus what you want to leave your heirs). This is where you determine your charitable capacity. Is there a cause or organization that moves your heart, and what might you do to help them?

As you head towards “home base,” decide on the timing of your gift. Do you want to see changes in your lifetime? There are many charitable tools designed to help make your dreams become reality and help charitable organizations thrive today and after you are gone. Be sure to add the charitable organization as a recipient in your Will.

Remember, “Memories fade, remembrances remain.” – author unknown

Phil’s discussion, Conducting the Conversations of Philanthropy in Turbulent Times, was very informative. If you are interested in receiving a copy of his presentation, contact C3 at info@c3fp.com.

™

™