Todd:

Good Morning/Afternoon, my name is Todd Healy with C3 Financial Partners. On behalf of my partners, Carolyn Smith, Celeste Moya and Rowe Blunt, we’d like to welcome you to today’s C&C Event.

We are all in the process of dealing with end of life events. Whether ourselves, with clients, family members, friends, or co-workers. Unfortunately it’s something we’ve all lived through and will all be living through. This morning we are very very fortunate to host Dr. Alan Chiu from UT Southwestern. He will help us anticipate what those events are like. Dr. Chiu has given us a pre-meeting overview of what he’s going to talk about. One of his key objectives is to make sure we’re not surprised by these events. Ashley Terrell will introduce Dr. Chiu, she works at UT Southwestern in the many different development areas raising funds across the medical center for palliative care. With that, I’m going to let Ashley introduce Dr. Chiu. We’ll have questions at the end, so please write in the Q&A.

Ashley:

First of all thank you for joining the call today to hear more about palliative care. If you have additional questions at the end, I am happy to help.

Broadly defined, palliative care provides specialized treatments for patients and families living with serious or terminal illnesses. At UT Southwestern, we truly excel in treating complex cases. Often that means patients have multiple conditions requiring layers of care and specialists. Managing chronic medical conditions can be a challenge. It’s really easy to see how a patient can end up feeling defined by that illness. As Dr. Chiu grew in his practice he recognized a need to care for patients with serious, often life-limiting diseases. While there was a focus on managing the disease, often helping the person trying to live with that disease was not a huge consideration. The central goal of maximizing quality of life at every stage of serious illness, even as patients cope with it, is essential to the aims of palliative care. While there’s a growing need for this approach, not everyone knows about it or understands it.

Today Dr. Chiu will explain palliative care and how it differs from medical treatment and hospice. He’s originally from Philadelphia, graduated from Swarthmore College before attending medical school at Jefferson Medical College. After his residency at University of Maryland in Internal Medicine he completed his palliative medicine Fellowship at University of California San Diego. Before he joined UT Southwestern two years ago, he led the palliative care team at Sharp Healthcare in San Diego. At UT Southwestern he is a member of our interdisciplinary team that includes chaplains, social workers, therapists, and doctors who specialize in palliative care like Dr. Chiu.

Alan:

Hello everyone! Thank you for the very kind introduction and describing a little bit about who I am. I apologize for any Dallas people since I’m from Philadelphia, I hope there’s no hard feelings.

I wanted to take this time to explain what palliative care is. It has been a passion of mine and it’s one that I think is really important for people to know and understand. I have a lot of items I want to go through. And I do want to try to leave time for questions at the very end.

The title is, “Supportive and Palliative Care: Focusing on What Matters Most.” Again, thank you so much for this opportunity to talk to you. It is a huge privilege.

For transparency, this talk is heavily influenced by a doctor who I dearly respect, Dr. Steven Pantilat, from the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF.) Dr. Pantilat uses the following analogy and I will weave it into today’s talk.

Imagine that you are on a plane 40,000 feet in the air. The engines are humming and you are lulled into a deep nap. Suddenly, the plane drops and shakes violently! You look out the window and see that the engine is on fire! You panic and think, “I’m gonna die.” That’s the feeling that you may have when told of a serious new illness. Such as: when you find out that the biopsy shows cancer; the test shows a massive stroke; one’s spouse has heart failure; you have dementia. And while it feels like one is going to die, it turns out that there’s a lot we can do to correct the plane to fly smoothly again. While no one will be able to sit back and relax any longer. You have to become the co-pilot. The plane may not stay in the air quite as long as originally planned. The destination may be different. But no matter how serious the medical news, you can usually get your life and that proverbial plane back in control. The plane can still land gently.

Every day I’m taking care of patients who have received this type of news. I have learned that we can live well in the face of all types of diseases. We walk alongside them. And I don’t mean just hope for a cure. I mean a sincere and heartfelt hope that I share with my patients. And one that I always wish was possible. But, I mean a broader hope that can coexist with the hope for a cure. I mean an achievable hope, a realistic hope. And I mean a hope that could be a path to a good life in the face of serious illness.

This is the preface for our talk and I’ll expand on all of this and how palliative care focuses on helping people live as well as possible, even in the face of serious illness.

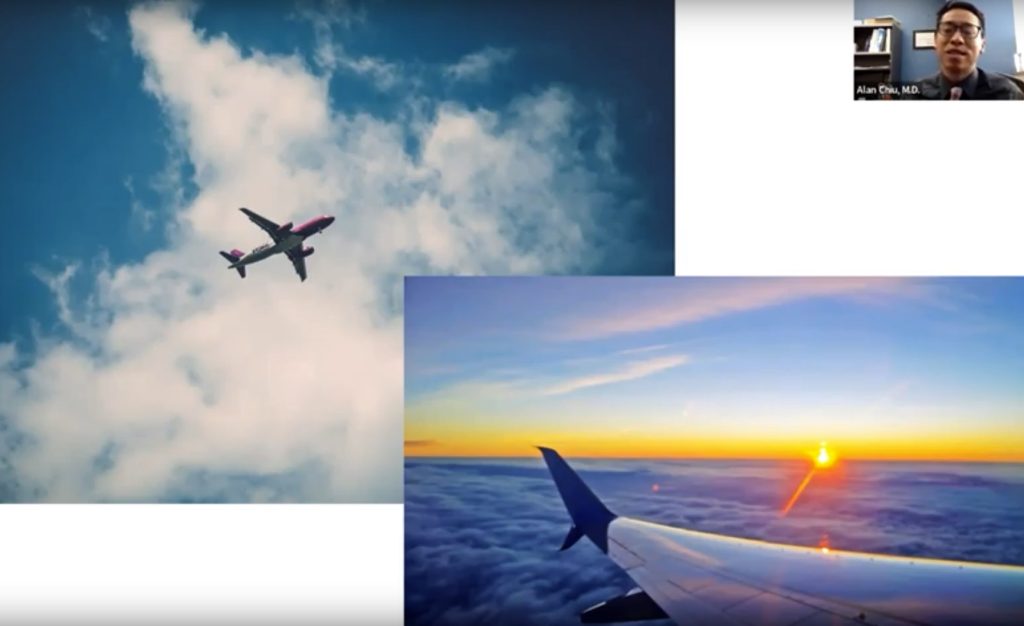

I want to start with some good news/bad news. Starting with the good news: there’s never been a better time to be alive if your goal is to be alive as long as possible. This is mainly due to public health improvements, better water, sanitation, good food and nutrition. Life expectancy has increased drastically over the last 200 years.

The bad news is that despite our best efforts, the death rate has still remained very stable and continues to be 100 percent. Unfortunately, there are no plans for that to change. That is the challenge that we face in medicine and as human beings. Life is full of wonderful experiences, relationships, and memories. Yet life is limited; this is the reality that we all live with. I argue that this is both a challenge and a gift. It forces us to spend our time the way we want, with the people we want, doing the things that are most important to us.

When we’re faced with serious illness and the reality that life is limited, that the death rate remains 100 percent, we are forced to face reality more urgently.

When we think about our health, it is interesting to think of things from a historical perspective. To see what longevity has meant for the way that we experience illness and even what we experience at the end of life. Let’s rewind 100 years, serious illness was very different because chronic illness was uncommon. Death was often sudden and unexpected so therefore we had a very different experience with serious illness and end of life.

I want to look at a couple of paintings. This is called “The Doctor’s Visit” by Gabriel Metsu.

This is very different from what care looks like nowadays. It is a person in a home holding the hand of someone who’s really ill. There are no IV poles, there’s no medication bottles, there’s no blood pressure cuffs.

The most famous is called “The Doctor” by Luke Fields.

In both of these scenarios, by modern standards, there is realistically little that these doctors could do to help these patients. They may have some idea of the cause of the illness, but there were no modern medicines, no life support machines, surgery was still a relatively brutal and a barbaric affair by today’s standards. Yet, the doctor is present with the patient in the midst of their illness. Facing it together.

When we think about what things look like in our current day, it looks very different than this for most of us. This is not what we would imagine when we think about our own end-of-life experiences. For most of us, it is not what we want. Yet, one in five Americans will die in the hospital and will spend time in the ICU. Statistically speaking, one in five of us will end up this way eventually. But it doesn’t have to be. We can take steps toward having a different experience of serious illness. A different experience of end of life than we may otherwise have in our current medical health care system. Despite all of its great advances, it can create its own challenges.

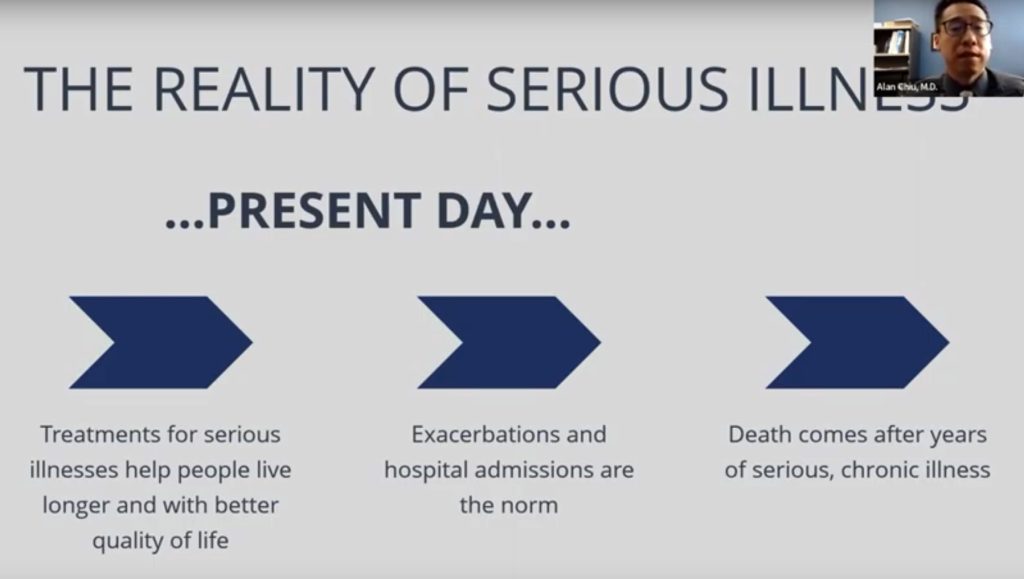

The reality of serious illness with present-day treatments for serious illness helps people live longer and with better quality of life.

There have been huge improvements our society has made in the last century, especially in the last decades. But it does mean that exacerbations and hospital admissions become more the norm. That means that death comes often after years of serious chronic illness. That leads to the own challenges that we have now.

A famous bioethicist, Eric Cassell, MD, summed it up this way:

“The relief of suffering and the cure of disease must be seen as twin obligations of a medical profession that is truly dedicated to the care of the sick. Failure to understand the nature of suffering can result in medical intervention that (though technically adequate) not only fails to relieve suffering but becomes a source of suffering itself.”

Too often, this is what we see. The medical treatments we offer to relieve suffering can become a source of suffering themselves. If we honestly look at what happens in ICUs across the country, we will see that many of the treatments used are contributing to suffering in the hope of relieving more suffering in the future. But as we become sicker, the chances of relieving that suffering goes down, while the chances of adding to the suffering become greater.

That leads to a situation where patients are at risk for care that is mismatched. Where people fail to receive care that they do want, and from which they will benefit. There’s a lot of studies that have tried to elucidate the things that people do want. They end up receiving care that they don’t want, things that aren’t priorities for them, and things that ultimately aren’t benefiting them. I’m sorry to say this happens daily in our medical system. This is not meant to be a critique of the medical system, or specific groups within health care, it’s merely the reality of an imperfect system, full of imperfect treatments, full of imperfect physicians and providers trying to care for people living complicated and unique lives. The consequences of these mismatches is that people and families can sometimes suffer unnecessarily. There are levels of suffering that are unavoidable in the face of serious illness, but there’s a growing acknowledgment that we have to do better to minimize the various sources of avoidable suffering.

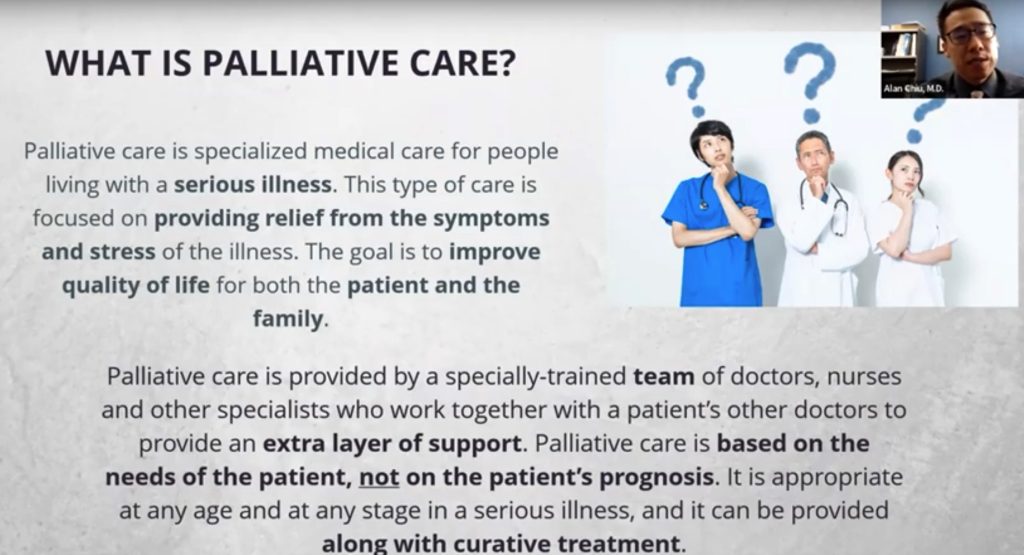

Now I want to talk about what palliative care is. This is a definition that is widely accepted. This specifically comes from the Center for Advanced Palliative Care.

“It is a specialized medical care for people living with serious illness. This type of care is focused on providing relief from the symptoms and stress of the illness. The goal is to improve quality of life for both the patient and the family.

Palliative care is provided by a specially-trained team of doctors, nurses and other doctors who work together with a patient’s other doctors to provide an extra layer of support. Palliative care is based on the needs of patients, not on the patient’s prognosis. It is appropriate at any age, in any stage in a serious illness and it can be provided along with curative treatment.”

So what is a serious illness? We have used that term a lot. It’s any of the scary stuff. Heart disease, heart failure, cancer, chronic lung disease, stroke, dementia, liver failure, kidney failures and other scary diseases that you will hear about. All of these diseases have scary life implications. All of these fall into the category of serious illnesses.

With that I’d like to emphasize a few things before I go on further. I want to emphasize that in palliative care, we embrace modern medicine. I celebrate breakthroughs that we’ve made as a country, as a medical field, to treat various illnesses both acute and chronic. I fight for us to continue to develop those new treatments. But we also acknowledge limitations. We respect the limitations of what health care can do to keep us alive and functional indefinitely.

We are patient-centered. We remember that people are more than their diseases, more than their illnesses. A patient is a person’s parent, a grandparent, a person’s child. That person is a sibling, they are a best friend, they are a spouse, they are a soulmate. They are spiritual beings, they are emotional beings, psychological beings, social beings. They’re not just their physical health and disease. So we cannot just take care of their medical well-being. But that’s the typical scope of modern medical practices – we focus on their physical health and disease.

A couple other acknowledgments. Our medical system is by default set up to do things. I don’t want to get into the weeds, but it is simply a fact that the momentum of day-to-day practice in medicine is: what is the next thing we need to do? What’s the next medication we give? What’s the next procedure we can do? Who is the next doctor we consult? What is the next thing I should do for this patient? What can happen is that this tower of cars can get stacked higher and higher. I’m often without a person who can help them constantly by evaluating whether this path that they’re on and where it’s leading them. And when we take a step back, we may end up in situations where we are inadvertently crossing a line of doing things to people, rather than for people. That risk gets higher and higher as people become sicker and sicker. The thing that I always want to emphasize is that for us in palliative care, we’re not in the business of ever giving up. We acknowledge that sometimes we can cure people, which is the goal for many people. But we are always caring for a patient, we’re always caring for them regardless of the circumstances.

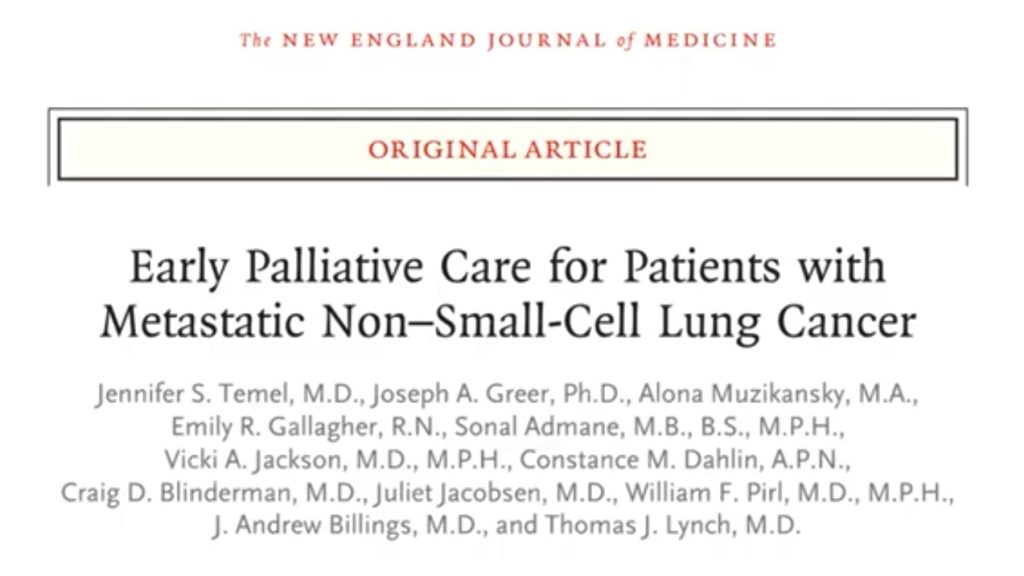

So those are some things that I wanted to emphasize before we move. I believe a famous 2010 study that encapsulates the benefits of palliative care. It’s in the New England Journal of Medicine. Probably the most famous medical journal we have. It shows that palliative care works. The study was done at Harvard and looked at about 150 people with metastatic lung cancer. In 2010 if you were diagnosed with metastatic lung cancer you had on average about nine months with chemotherapies. It was a really bad disease back then. All the people received gold standard chemotherapy, half randomly assigned to receive palliative care at the same time as chemotherapy, the other half just getting standard care and chemotherapy. They found that everything good we want to have happen to people-better quality of life, less depression, less shortness of breath, longer survival-all of those things happen to people who also got palliative care. The people with palliative care lived longer, on average by three months. It was about one year for the group that got chemotherapy plus palliative care. It averaged about nine months for those with chemotherapy alone.

Cancer treatments have continued to evolve and improve. But the basic findings of the study remain the same. Palliative care helps people with serious illness live better. If you, or a loved one, has a serious illness, you should make sure that you ask for palliative care. Don’t take no for an answer. You’ll inevitably have someone tell you that maybe it’s too soon, or that you’re not ready yet. Insist. For us, in palliative care, we know that we can help people live as well as possible, for as long as possible.

So who’s it for? It’s for all ages, it’s for all stages of serious illness. Again, don’t let someone tell you it’s too soon for palliative care or that you’re not ready for palliative care. It’s for all settings, the hospital, I underlined and bolded HOSPITAL because that is where palliative care is most established. It is where it historically has been around for the longest. Most hospitals have some form of palliative care, they may not have the full version of palliative care (which I’ll explain later.) That’s where most people will get their first exposure to palliative care. It is also provided in the clinic, mainly in major hospital systems will they have a palliative care clinic, but that’s an area of constant growth. Home is unfortunately the area of least development for palliative care. Despite it being the place where anyone who is currently going through serious illness or who has gone through serious illness home is the place where they need this type of support. The hospital systems are starting to see that that’s the case, and so it’s an area of growth, but unfortunately apart from hospice services (which is a separate piece) it’s really limited at this point in time.

Who are we in palliative care? The top photo is a portion of the Clements Hospital palliative care team. On the bottom is a portion of the Parkland Hospital palliative care team. But a person, as I mentioned, is not defined or limited to their medical problems – they are their physical health, their physical beings, social, psychological, spiritual, cultural, emotional beings.

So we have an interdisciplinary team to address all those parts of a person’s health and well-being. It includes physicians, nurses, social workers, chaplains, and depending on the maturity of the program, child life specialists, clinical psychologists, pharmacists, music therapists, pet therapy, counselors. There are different forms of palliative care teams all over the country. What we focus on are these three major categories:

- Symptom Management.

If we’re serious about helping people maximize quality of life we take their symptoms seriously. It is impossible to have a good day if you’re in pain. If you’re constantly nauseated, or God forbid, if you’re feeling severe shortness of breath. That is one of the worst symptoms I can imagine. We use medications that can sometimes be uncomfortable for other providers to use, but we do it because many times that is what is necessary to help people still accomplish their day-to-day goals. Sometimes that’s what is necessary to get them to even make it to their next appointment. To be able to continue with their next infusion, to be able to get their next treatment. We need to control people’s symptoms to be able to give them a semblance of quality of life in their day-to-day existence. We also focus on communication and prognostication. Doctors are terrible communicators. We use highly technical language, aka jargon, but it’s highly specific in what it means. We are terrible at making sure the patients understand all the nuances and implications. It’s biased, providers are biased. They may not feel comfortable saying things explicitly. Communication is fractured. Patients are often hearing parts of something from one doctor, or parts of something else from another doctor, and they’re the ones trying to put together the whole illness and the whole story together on their own. And that’s unfair, because it could be a challenge for even a good doctor to do that themselves because things can get so complicated. Then we’re leaving these patients and families to try to piece it together themselves. Doctors get zero formal training about communication. That is changing with the new batch of doctors, but historically there’s been little to no training for doctors on how to effectively communicate. That’s scary, considering how high the stakes are in medicine and prognostication. Communication is something that us in palliative care take very seriously. The questions of, “Doc how long do I have? What’s going to happen to me next? What are things going to look like three months from now? What are the chances that I’ll survive this?”

- Then we have prognostication.

Prognostication is difficult, and doctors don’t like to do it. But people want to know. And if they don’t know, they’ll start to infer. But these things are too important to be left to just inference. I can’t tell you the number of times I’ve had patients tell me this. I can’t tell you how many times I had situations where either the person believes that they only have weeks to live, when in actuality, they have much longer. Or the opposite situation, where they believe that they have years to live, when in reality that time is much shorter. Again doctors are often afraid to talk about these things. Often, patients are afraid to ask. But since we’re in the business of realistic and true hope, we spend a lot of time trying to guide these families in what are realistic time ranges. Then they can make the best decisions for themselves. We try to offer realistic expectations so that they know how to be prepared. Imagine how different a person’s decisions would be if they found out that they had weeks of time vs years. Imagine if they found out that they would likely end up being bed-bound in the near future. These are things that a lot of times doctors know. They may not know these things for sure, but they’re worried that these things are happening. These are hard things to talk about, so oftentimes they just don’t get talked about. That’s why palliative care takes this skill of prognostication very very seriously.

- The third thing of focus is planning for the future.

We don’t know what’s going to happen in a lot of situations. We have our worries, we have our understanding of what our best-case scenarios and our worst-case scenarios are. We want to make sure that patients have the ability to plan for the future. Especially if they’re diagnosed with something that we know has a predictable course, has a predictable pattern. That is where advanced care planning can come in as I’ll talk in future slides.

I want to emphasize that palliative care is not only end-of-life care. As diseases progress with time, the need for palliative care typically does increase. As the complexity of care increases, it can lead to increased stress from the patient and family and the need for more careful and clear communication. Palliative care is in there helping with that. Their symptoms often worsen: the pain, the nausea, the shortness of breath, anxiety, depression, confusion, fatigue. Palliative care is in there trying to help them manage those symptoms.

Sometimes, we can end up in situations where the care is not aligned with, or focusing on, the things that matter most to that person. Where their hopes and their goals are not being met. That is when palliative care is in there. The person can have many different goals and some are more achievable than others. Some are more of a priority than others. Sometimes we have a hard time figuring out which goals to grip onto, and which ones to loosen the grip. It may be harder to stay focused on the things that matter. We may end up being too focused on goals that may not be realistic. They may come at the cost of goals, which in hindsight, or the hopes that we could have been focusing on all along, or maybe even the foundation upon which that other goal that we were holding on was so tightly based on.

I think of patients who are so focused on trying to fight an incurable disease, heart failure, ALS, dementia. They are doing that to be able to be alive for their family as much as possible and for as long as possible. They keep on fighting to pursue that next intervention to try to reach that goal. They end up spending days, weeks, months in the hospital – away from the people that mattered most. It is almost that these two goals can increasingly become in competition with each other. The next thing we can ask ourselves, how do we get here? I’m not saying that this is the situation for every single person. With palliative care, we care deeply about each person’s goal. For some people, that goal is to try everything to fight the disease to the very very end. And we’re supporting those patients with palliative care. We try to treat those symptoms so that they keep fighting. But oftentimes there is this other situation that happens where patients are asking themselves, and their families are asking themselves, how do we end up in this situation?

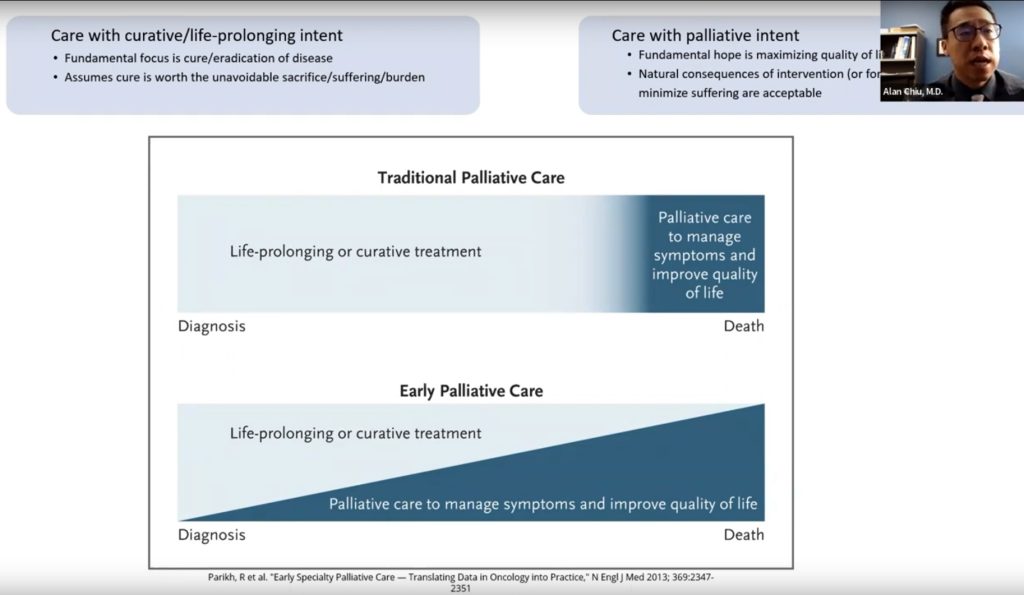

Oftentimes this is the old model of what palliative care used to do.

If you look at this traditional palliative care diagram, on the top there are two paradigms. One is care with a curative or life-prolonging intent. The other is care with palliative intent. When there’s curative or life-prolonging intent, then there is a fundamental focus on a cure, or the eradication, of the disease. I would argue that focus is even possible while trying to manage disease. But it assumes that the cure is worth the unavoidable sacrifice, suffering, or burden that comes along with it.

The opposite side is the care for palliative intent where the fundamental hope is maximizing quality of life. With the understanding that there are natural consequences of intervention or foregoing intervention to minimize suffering that became accepted. With this old model we put the pedal to the metal for as long as possible until it becomes obvious that the treatments are not helpful anymore. At that point, we typically do a 180 degree turn and focus on care that prioritizes comfort. But the problem with this old view is that it does not account for the fact that in serious illness, oftentimes there’s a predictable course to it. This “all or nothing” view means that oftentimes by the time we’ve reached a tipping point, the proverbial plane is already in its tailspin. The opportunity to have a gentle landing may not be possible anymore.

All too often, this is the experience that people have when they’re dealing with chronic seriousness. And this is why I’ve been moving slowly towards an alternative focus, where palliative care gets involved much earlier. Then, as time goes on, the focus can shift away from away from less and less care that is focused solely on trying to eradicate or cure the disease regardless of the cost. There’s more and more emphasis on how we can start to focus more on quality of life as time goes on. Ideally the two connect in parallel, but in the setting of progressive illness that tension is at the heart at some of the most difficult crossroads that people do face. When they are at those crossroads, palliative care is in there with them trying to help navigate.

I want to talk about a story that will demonstrate some of the ways that palliative care can be helpful.

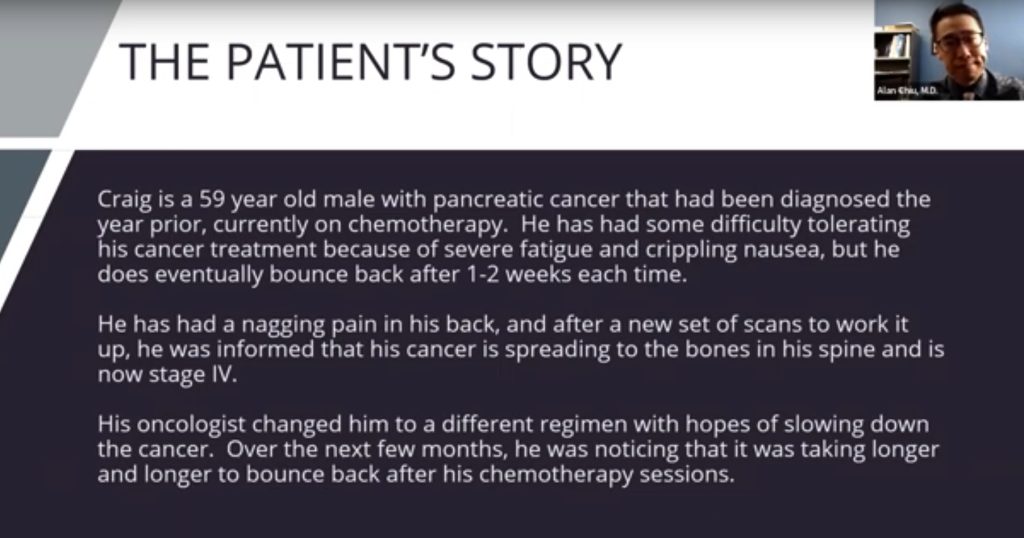

Craig is a 59 year old who I took care of a couple years ago. He was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer a year before I met him and he is now in chemotherapy. It was pretty hard for him. He was developing a lot of fatigue and really bad nausea when he would get his treatments. But he had eventually bounced back after about a week. I was seeing him trying to manage his chronic pain. He started describing this really bad back pain that was getting worse and worse. So I referred him to get some more scans. Unfortunately, it showed that it had spread to the bones in his spine. It was now stage four. The oncologist changed up his medications hoping to slow down his cancer. Over the next few months I did notice that there were some changes. He was having a harder time bouncing back. I saw him in the clinic and noticed he had a different aura to him. I started diving in. I asked him some questions like, what have the doctor’s been telling you? He replied that they had changed up his chemo and he was hoping for the best. I asked him, “Did they tell you what the best could be?” Craig said, “Well, my doc said that there’s about a 40% chance that I can have a response, so you know, I’m taking my chances.” I asked him, “Did they tell you what things would look like if you’re in that 40%?” He replied, “Well, no. I didn’t ask specifically. I assumed that it would mean that I could feel better again and I can go back to living a normal life.”

Now I’ve been doing this long enough to know that once someone is diagnosed with metastatic pancreatic cancer, even if they do respond to treatments, a lot of times the treatments are able to prolong life, but it’s often only in the range of months. Compared to without treatments there is a good chance that a portion of that time could be spent in the hospital dealing either with complications from the cancer itself. Or from the very chemotherapy that we’re trying to treat the cancer with. And I could have gone along. That would have been the easy thing to say, “Yeah, I hope so too.” But is that something that I believed would happen with all my heart?” Did I believe he would be able to go back to living a normal life knowing that version of a normal life? His normal life was traveling and golfing almost every day. He was a very lively and active person. I knew that wasn’t going to be what the next months and possibly years would look like for him. If I allowed Craig to believe that there remained a chance that he could overcome cancer, while knowing that his cancer was in an incurable state and that it would eventually cause his body to get weaker and weaker, then what I’m giving him is not true hope, but a false hope. In the end, false hope is no hope at all if it is not based in reality. You may think, what’s so bad about some false hope? What harm will it do? Well, it can make some people think that their future looks different than what it’ll actually look like. And they may make both medical and personal decisions then may be different.

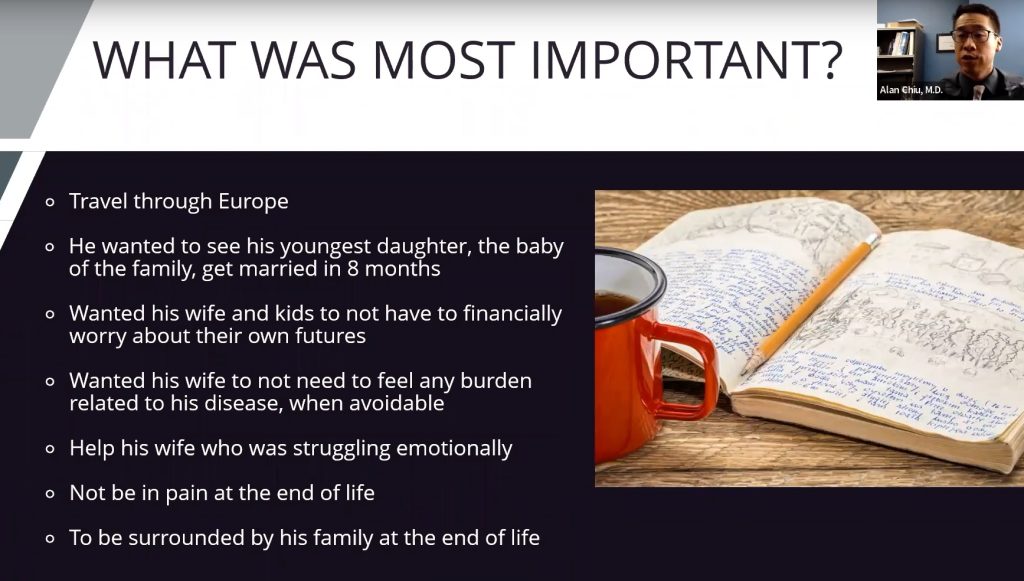

So I sat down with Craig and we talked. I dug in, “Hey, tell me more.” You know, every time someone comes into the clinic we go through all of the things about their life. Their hobbies, their family, their faith, all these things, we dig into with them. We reviewed all these things again and a couple things were clear.

He wanted to travel through Europe. He had a few places he wanted to travel to specifically. Particularly going to him and his wife’s favorite cafe in Paris. He wanted to see his youngest daughter, the baby in the family, get married. Her wedding was planned in about eight months. He wanted his wife and kids not to have to worry financially about their own futures. He wanted his wife not to feel any burden related to caring for him if possible. And he wanted his wife, who was struggling emotionally with his disease, to be okay. He wanted for himself to not be in pain. And he wanted to be surrounded by his family at the end of life.

I listened to him and I grew more and more worried that his window to travel was getting smaller and smaller. I knew he would not have been able to do these trips while he stayed on chemo. Because I know the toll that the chemo would take on his body. I knew the laundry list of appointments and lab tests and imaging that he would need to keep up with. I also knew that his daughter’s wedding in eight months was not a great timeline for him. So I messaged his oncologist and we talked honestly about what to expect. We reviewed the details of his cancer and we realized that even though the cancer treatments may be giving him the best shot to live as long as possible, they were not necessarily going to help him live as well as possible after we unpacked all of the details. To achieve those things that give life the meaning that makes it worth living, the oncologist and I worked together with Craig. We met the oncologist who is the expert on cancer, Craig who is the expert on him and what means most to him, and myself acting as a bridge between the two. I was the bridge who understands the medical complexity, while also having taken the time to understand who Craig is. Together we decided to forego further chemotherapy.

And you know what? He was able to make it to Paris. He wasn’t able to make it to some of the other countries that he was hoping to. He had to cut his trip a little bit short. But he was able to do it. And his daughter decided to move their wedding up to about three months. They had a small wedding and he walked her down the aisle.

Craig was able to make some financial decisions that he hadn’t originally planned on. He knew that his wife hated dealing with real estate and all that. So he decided to liquidate some of his assets to make sure that she felt like she had all that she needed. And she was able to make sure that she was getting counseling because he knew that this was going to be hard for her. He rolled onto hospice and about four months after that decision to stop chemotherapy, he died at home with his family.

What we do in palliative care: we do medical things, we do medications, we refer for procedures but the treatments we do are often more than medical. We help patients in a way that no medicine is going to fix. We help them achieve things and no medicine is going to be able to help them.

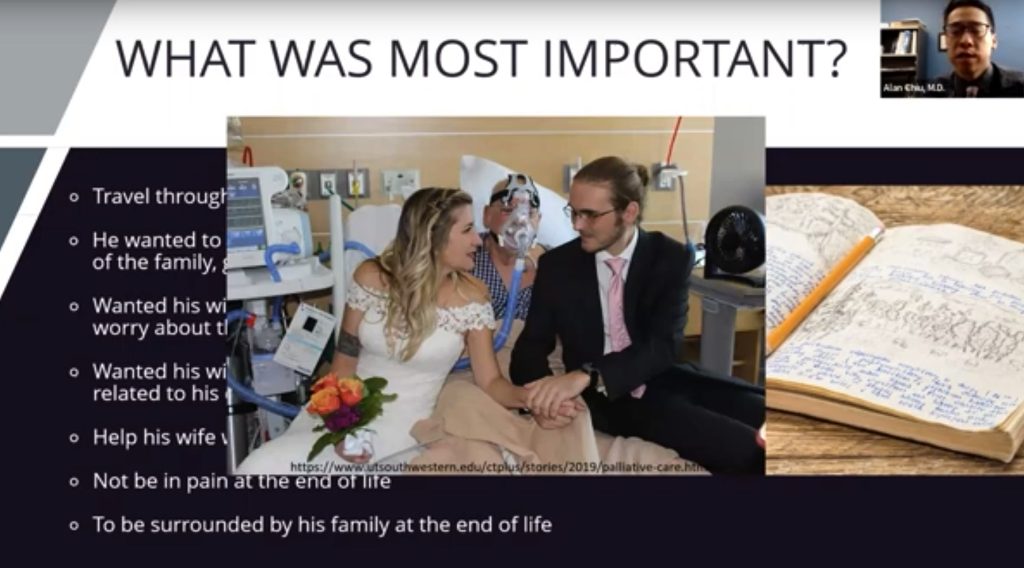

This picture is another family from 2019.

Mr. Hayes, the gentleman in the middle, was dying of lung cancer. His wish was to be able to see his only daughter get married. The palliative care team worked with Clements University Hospital and UT Southwestern. They converted a couple of the neonatal ICU rooms to changing rooms for the bridal and groom parties and they had the wedding in the hospital. Mr. Hayes was able to see his daughter get married and he died three days later.

We know that people are not just their medical illnesses. That’s what we do in palliative care.

When you think about the future, what do we hope for? If we are not careful, if we are not intentional, we may pursue and accept treatments that are more likely to harm than to help. We may miss opportunities to achieve what is possible. While we may not be able to achieve all of our goals, all of our hopes, there are many that we can still achieve. We can experience joy, calm, gratitude and love. And when the time comes, we can hope to land the plane gently.

Too often in medicine, we ignore the fact that every plane must land. That every life must end. Instead, we think we can just fly the plane around and around. We think that as the fuel gauge goes down and we’re still flying when the plane engine goes out and we’re still flying the plane until we’re out of fuel and the plane crashes and burns on the ground. How much better to savor the flight, and as the fuel gauge goes down to land the plane gently?

Again, it may not be a time that you thought it would be. It may not be at the destination that you thought it would be. But with work and intentionality we hope it’s on the best terms possible. We hope to focus on the things that make life worth living.

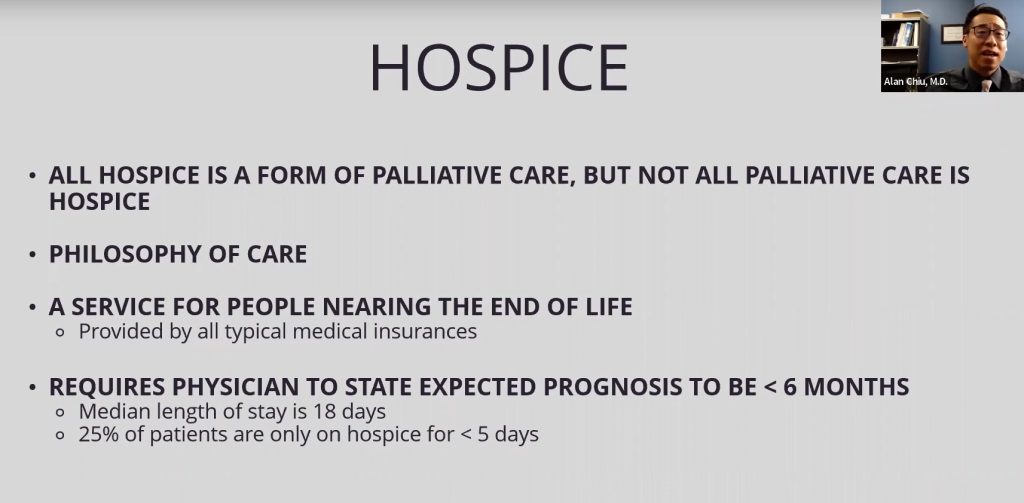

I want to transition to some practical matters. I have spoken a lot about what palliative care is, and that it’s not hospice. I do want to touch briefly on what hospice is.

All hospice is a form of palliative care, but not all palliative care is hospice. Hospice is a philosophy. A philosophy that shifts away from things that are going to add any further burden or stress on the patient. Whether it is going back and forth to the hospitals, or the ER, or the clinics. Getting blood draws, getting tubes, or artificial means of supporting the body. Instead, hospice is focused on ensuring that any symptom that can get in the way of a person having the best day possible, that their body will allow it, that those symptoms are managed, and that they have as much support at home as the medical system will be able to provide. It’s a service for people who are nearing the end of life. It is covered by all the typical medical insurances. It requires that a physician state the expected prognosis to be less than six months. Many times it’s longer, many times it’s shorter. The median stay for someone on hospice is about 18 days. The unfortunate thing is that about a quarter of patients are in hospice for less than five days. The general refrain that I hear from families is that they wish they were in hospice sooner. It’s provided in the patient’s preferred setting, wherever that may be. Assisted living facilities, skilled nursing facilities, a dedicated hospice facility, or for most patients, at home. They focus on symptom management. 24/7 access to the hospice team force of the management. They focus on the things that are the most meaningful goals of the patient and family.

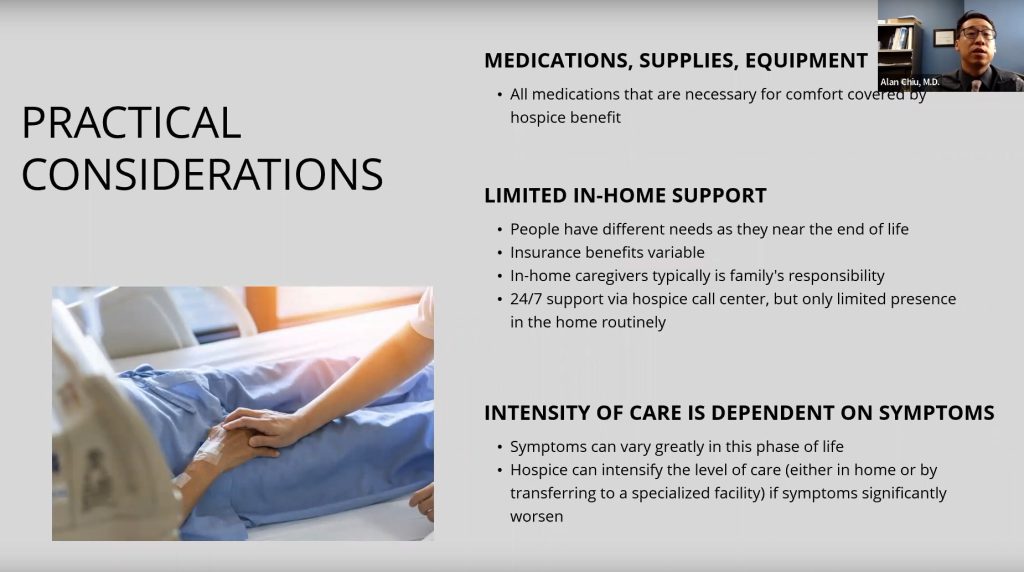

Some practical considerations for people in this phase is that medical medication supplies and equipment are provided by the hospice team. The hospice team which includes a doctor, social worker, chaplain and nurse. They take over all of the care. Sometimes if a primary care doc wants to be the main one still coordinating they can, but it all typically gets coordinated under one umbrella. This makes things easier for the family. But there is limited in-home support. People have different needs as they get to the end of life. Different insurance situations, some have long-term care insurance. Depending on the specific type of health insurance there is some home support. But as a general rule of thumb, in-home caregiving is typically the family’s financial responsibility. Hospice does provide 24/7 support via their call centers. But typically in-person care is only about a few hours a week. There are caveats since the symptoms can depend greatly from person to person. Since the main goal of hospice is to make sure that they can be comfortable, so if their symptoms intensified to the point where they need a nurse to physically be in the house for many many hours, or if they need to be transferred to a specialized hospice facility, that is all part of the hospice benefit.

Everyone’s story on hospice looks different. Depending on how late they come on the hospice service. Depending on how early they come to the hospice. Depending on what their symptoms are like. Everyone’s experiences on hospice can be different. Just like how every person’s story is different. But that is the best tool that we have to be able to help people land gently.

I do want to talk a little bit about preparing for the future.

We are used to preparing for things that may never happen to us in the course of our lives. In Texas, we have tornadoes. For those close to the gulf, seasonally they prepare for hurricanes. We’ve all sat through flight safety instructions. These are things that, realistically speaking, we will seldom have to implement, but that’s not the case for planning for our inevitable passing. There are practical ways that we can do it.

I’m going to briefly touch on some of the legal documents, I’m going to talk about some of the pragmatic things.

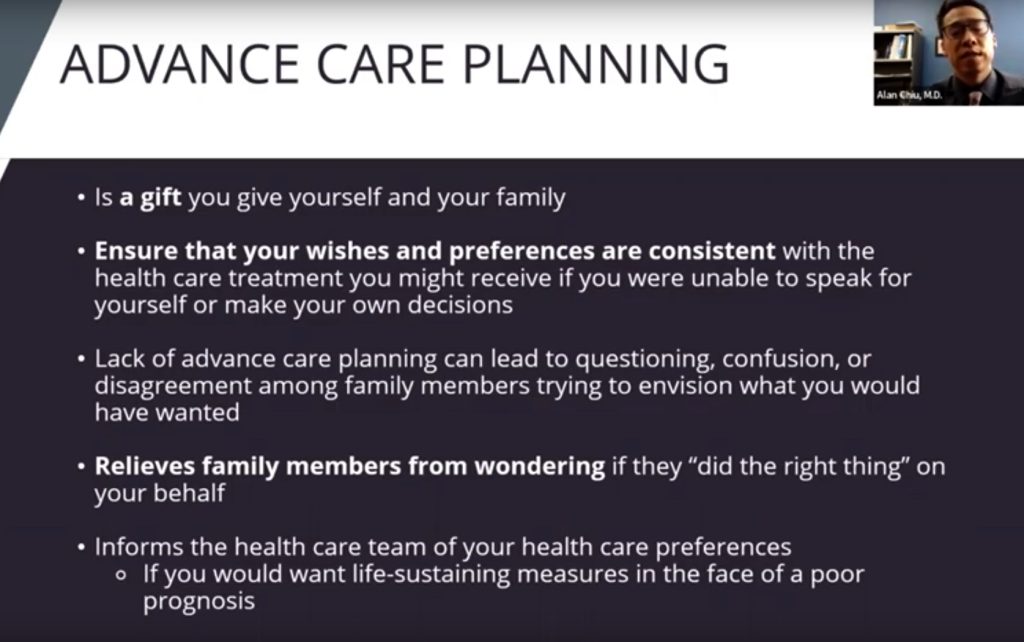

Advanced Care planning is essentially a way for you to explore and document your wishes for your family. Therefore the burden of decision making doesn’t fall on them if you’re not able to make decisions for yourself. There are ways that you can do this formally. When they are done formally they carry medical weight. There is a moral distress that comes with having to talk about these things. If we don’t help our own families know what it is that we want, we are unintentionally placing the degree of burden on them to have to make these decisions on our behalf. So these documents can take away some of the burden and share that burden.

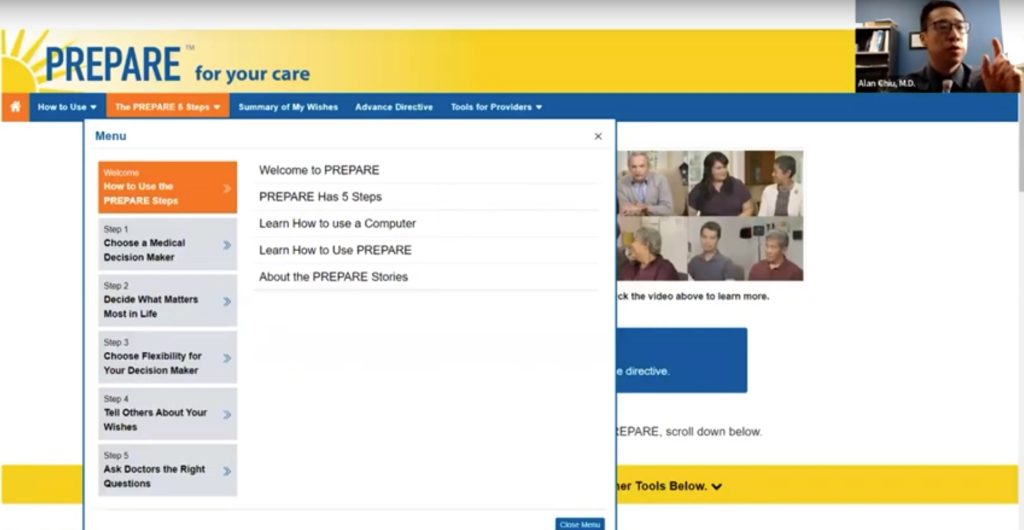

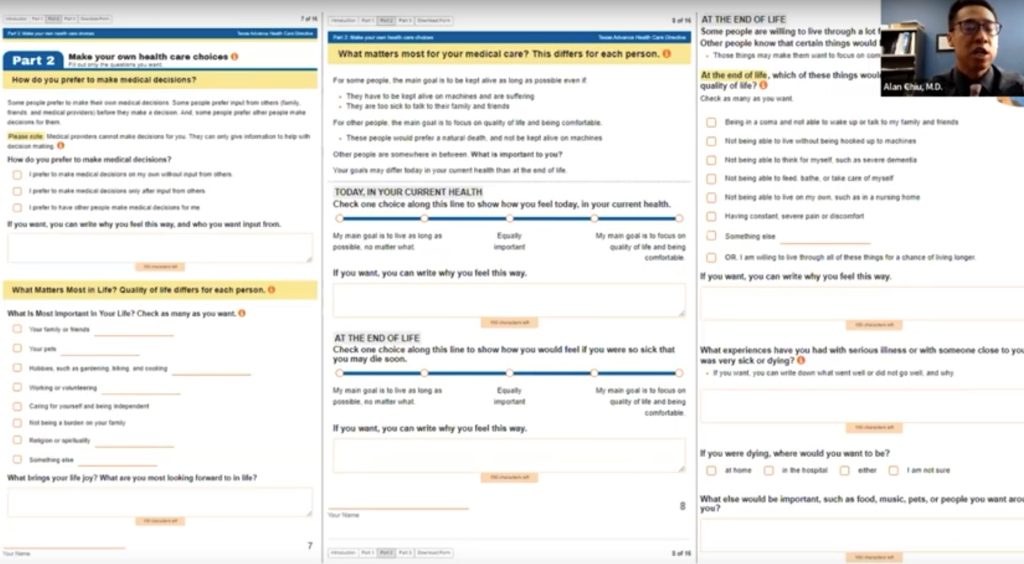

Obviously this is part of what estate planners do. I personally have found “PREPARE for your care” which is a resource based out of UCSF to be a very user-friendly resource for anyone that you want to encourage to go through this process. They really go through it.

There are videos and they walk through it step by step.

It is very user friendly and it will present documents at the end.

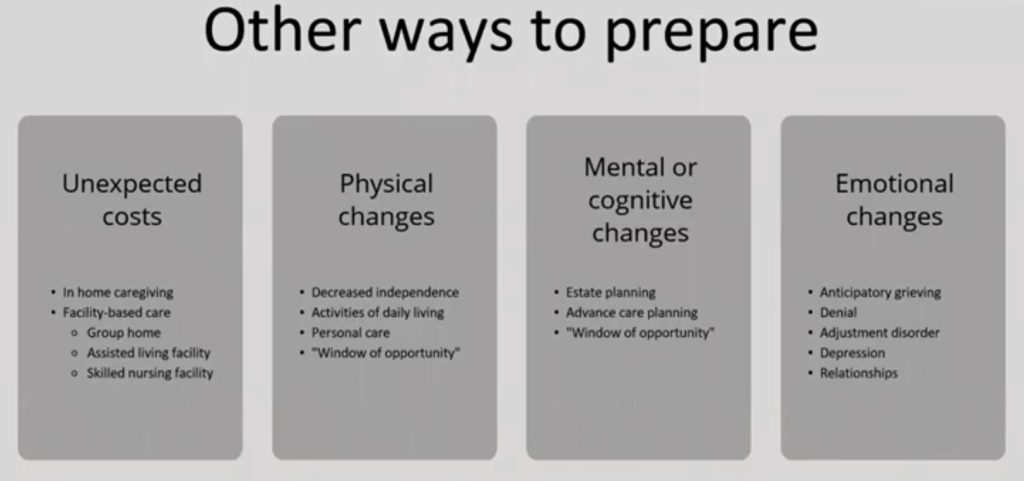

But there are other ways that we can prepare. There are unexpected costs that come along with this unpredictable phase of life.

I mentioned some in-home caregiving. Based on national data, it can cost anywhere from $25 to $30 per hour. If you were to have someone full-time during daytime hours that’s easily fifty to sixty thousand dollars a year to have private care for about 44 hours a week for 52 weeks out of the year. If someone is there full-time, 24/7, that obviously will be higher. Many times some people just need help at night so that they can get rest. That tends to be a little bit less – often in that range of $150 to $250 per night. There are different permutations, but this is often not covered by insurance.

Then there’s different types of facility-based care group homes. This option is probably the least expensive. This is a home that is occupied by multiple people. Typically there is some sort of nurse that oversees medications. It gives people a shared space to live in.

There is an assisted living facility which prefers patients who still have some degree of independence. There are nurses that are available. They do help with some degree of medical management but they are able to perform most of their independent activities themselves. This option is a little bit more expensive, the medium is typically about four thousand to five thousand a month. Obviously the better the facility, the more expensive.

And then there are skilled nursing facilities. This option is probably the one that most of our patients and families don’t know how to budget for. They also don’t know what to expect. Based on current 2021 data for Texas, the cost is about sixty-two thousand dollars a year, or a little over five thousand dollars a year for a semi-private room. We’re up to $7,000, almost $7,100 a year for a private room. This cost is increasing quickly – more than inflation. By 2030 many predict that this could easily be the six-digit number per year. This is something that many people don’t prepare for when they’re dealing with a serious illness.

The reason is that it can lead to this next topic – physical changes. People will become limited in their ability to do their daily living activities – such as feeding themselves, washing themselves, bathing themselves, or personal care. The thing that a lot of people don’t think about is this window of opportunity. We have a tendency to push off goals because they think “I will get to later. I will get to it after I finish this treatment.” But when we’re dealing with a progressive illness there is a window of opportunity that gets smaller and smaller.

Then there’s the mental changes that come along with the physical changes and that can lead to more and more difficulty doing estate planning or doing advanced care planning. The mental changes can oftentimes be just as limiting at reaching those goals.

Then there’s the emotional changes. The grief, the denial, the adjustment of depression. This is where palliative care tries to help.

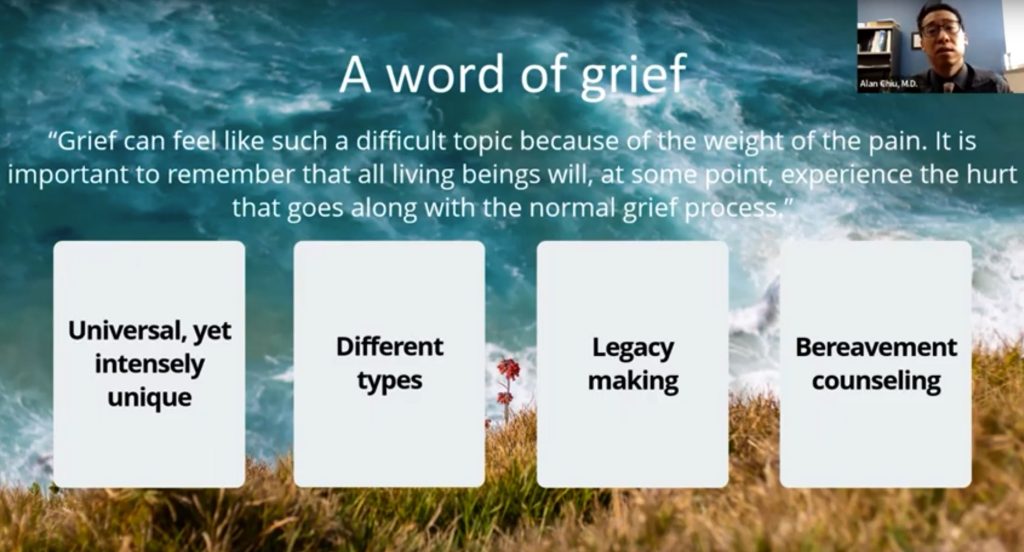

I want to put a word in on grief. It is a difficult topic because of the weight of it.

We all experience hurt that comes along with a normal grieving process. It is universal, despite being intensely unique. There are different types of grief. There is absent grief, anticipatory grief, complicated grief, delayed grief. There are ways that we can try to chip away at the normal reaction that is grief. For those of us in palliative care we care a lot about legacy making. I’ve helped many patients make video journals. I’ve helped patients work through their pain and symptoms so that they can write their books. There’s little ways that we can try to restore humanity to them, even when they feel like they’re a different person than they were before. I’ve had people knit or quilt a blanket to be able to give a grandchild that they would never be able to meet.

Then there’s bereavement opportunities. For us in palliative care, even though we’re taking care of patients, many of whom are able to overcome their serious illness, but many of our patients unfortunately don’t. We have bereavement counselors who follow along with patients.

On a personal note, things that I’ve found helpful – I am a tried and true Presbyterian and I have found many books that I’ve found personally helpful through my own journey of grief for family members and my own dad who died this past year. I always make a plug for the book, “Grief Undone, a Journey with God and Cancer,” written by Elizabeth W. D. Groves and Al Groves. Al is one of the professors at Westminster Theological Seminary. There are a lot of resources out there for grief. I believe there’s another talk that C3 gave talking specifically about grief.

I would like to wrap up.

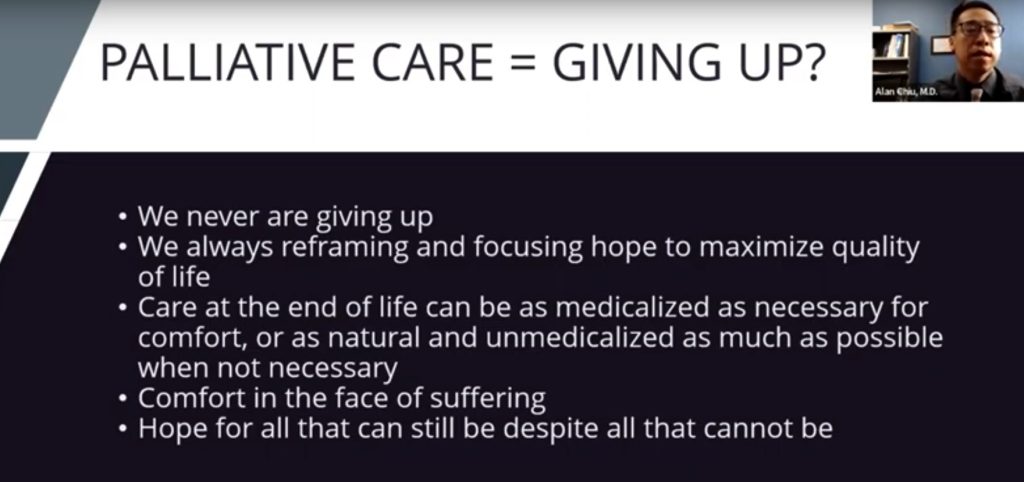

Palliative care – we don’t give up. That is not what we do. We are in the business of reframing and focusing on the hope to maximize the quality of life. We hope for all what can still be despite all that cannot be. I believe that sums up much of what we do. It’s not end of life care, though it does include all stages of illness. We focus on the person and are person-centered care.

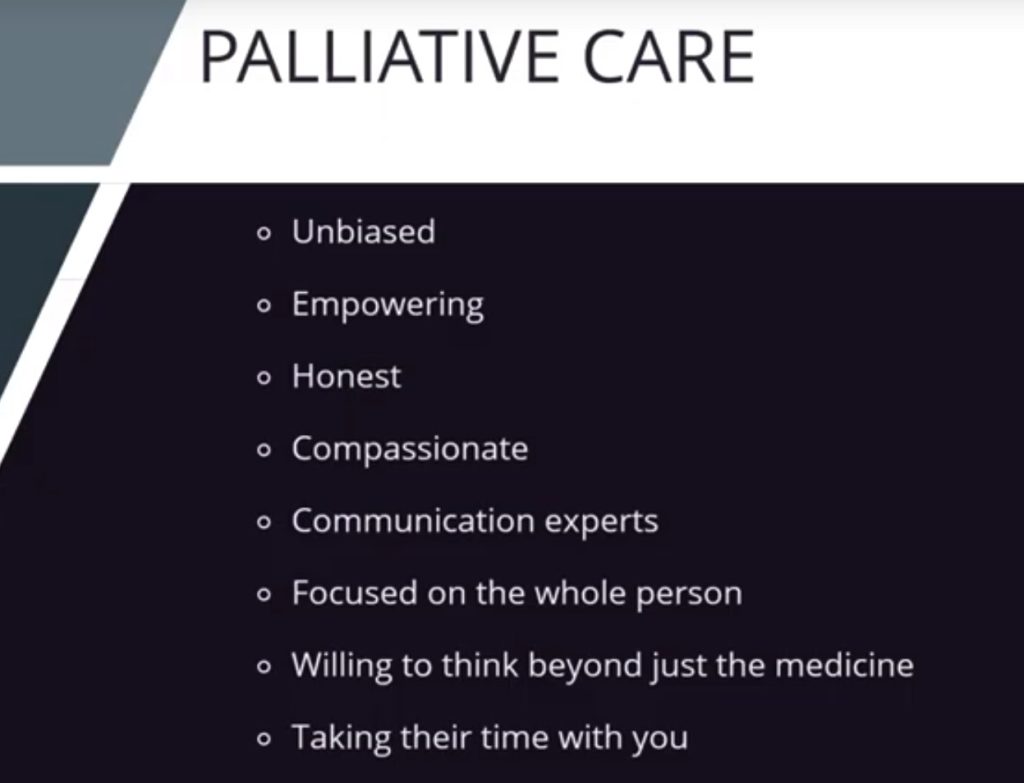

We are unbiased. Because we are person-centered care, we don’t bring our own biases in. We may have a patient whose family does not want to go through the same process that happened with another loved one. I need to be able to clear myself of all those things when I’m talking to a different person who may have a completely different set of priorities. We empower patients, but we are also honest with patients. We’re not in the business of false hope. We are compassionate. We are experts when it comes to communication. We focus on the whole person. One of the things that our patients notice most is that we take the time. It is not uncommon for us to spend an hour to two hours with patients listening to them and learning about who they are.

I may seem like a young man, but I have walked alongside countless numbers of people – both young and old – through some of the most difficult circumstances. I’ve seen things go well medically and I’ve seen things go poorly medically. Regardless of how things play out, we in palliative care will always focus on walking alongside any patient with serious illness. We will take the circumstances, however hard it may seem, and work with patients and families to try to right the plane and continue the ride as smoothly as possible, preparing them for the turbulence that we know is coming. And when it’s time, to land the plane as gently as possible.

With that, thank you so much for your time. I welcome any questions that you have.

Todd:

Dr. Chiu, thank you so much. I’m thankful that we were not on camera while you were making your presentation. It was very very powerful. Thank you for helping us prepare for that landing.

I know there are two or three people on this call who have recently gone through something very similar to what you’re talking about.

I obtained permission from Ed before I asked him to do this, he’s recently experienced palliative care with the care of his son.

Ed:

Thank you, Todd. And thank you Dr. Chui, this was a wonderful presentation. Very comforting and comprehensive. I wish you had been involved with my son, Drew. January last year he was diagnosed with stage four pancreatic cancer. There was no pre-warning. That was the first diagnosis. He died a month ago yesterday. He had been in hospice for the time that you mentioned – about two weeks. And that was the notice. He was at MD Anderson in Houston, where he lived. Candidly, I do not think that the palliative care for him was very strong. While all of these cancers are terrible and his certainly was. He didn’t experience a lot of excruciating pain, yet he was very uncomfortable. He had a port for his chemo treatments at home. He went through a chemo trial with the drug, Lynarsa. Then chemo again. His lab counts, which I never fully understood, were up and down until finally they took a bad turn. I saw the coordination of his palliative care team led by Dr. Tung Shu. His first diagnosis came in January 2021 when Texas had the power outage. Plus, COVID. For a time, a doctor could not physically see him in person. We were remote. We were remote enough with him being in a different city, but his wife couldn’t go in with him during the early stages because of COVID. And I couldn’t go in to see the doctor physically with him. As a lawyer I’ve certainly been an observer and involved in a number of situations that ended in the same way.

But I felt much of the atmosphere that you talked about Dr. Chui. No one specifically told us the timeline of the prognosis, unless my son shielded us from that, I don’t know. But from what I’m told with pancreatic cancer stage four, he was on the long end. He lasted a lot longer than most. He was at home, which you mentioned was a tough place to have palliative care, surrounded by a wife and three children ages 18 on down. He was comfortable, he had been working from home, so he was able to work during a period of time.

The hospice care was gentle and his mind stayed good. You said everybody’s situation is different. Every one of these situations is terrible. I wish we had palliative care. Although his family progressed pretty well through this, I can see where the communication on a frank and informative level to all concerned, could have been better. I’m very impressed and struck by the wisdom of your remarks Dr. Chiu. I don’t know if I have anything else to add. Except that hospice was gentle and we were all there with him. He died three days after his 52nd birthday. He was a person of faith, which as you mentioned, helped immeasurably on his path.

Dr. Chiu:

Thank you for sharing Ed.

Todd:

Thank you, thank you very much.

I think a couple of my takeaways are:

Number one, Dr. Chiu comments about false hope. That was such a powerful lesson. Being realistic and being able to ask those questions. I bet everyone on this call has been through at least hospice, if not palliative care. And being able to ask those questions and deal with it realistically is vital. Had you not helped your patients Craig and Mr. Haynes, they wouldn’t have been at their respective daughter’s wedding. So false hope would have really been dramatic.

The second takeaway we’d like to thank you for is the booklet you referred to, “Preparing for your Care.” That’s a great resource.

This presentation will be on our website and we’ll have it on our LinkedIn posts.

We hope it’s a tremendous resource for others.

Dr. Chiu, I tell you I thought I understood palliative care, but I had no clue. So thank you for clarifying. I believe your presentation will be a gift to not only those of us on the call, but for those who view it later. To your point of “preparing for the landing” you don’t wait until you get to the landing strip to determine how you’re going to land the plane. We are big believers in preparing. We talk about the fact that five months too early is better than five minutes too late. So we thank you very much again for that presentation.

We will have another C&C Event in January. It will feature Mike Kiolbassa from San Antonio. He runs Kiolbassa Meat Company, a third-generation company. He is going to talk about taking a company from a family-operated business and a family hands-on business, to an international company where the family is now in charge of running the business as opposed to operating it themselves. I’ve heard him before and he is a very good and powerful speaker. We’ll get the dates out in advance.

Again, Dr. Chiu, thank you so much. Ashley Terrell, thanks for the introduction.

We hope the rest of you have a great week.

Thank you, goodbye.

This presentation explains the value of the field of Supportive and Palliative Medicine to individuals and their loved ones. We discussed how our interdisciplinary approach supports patients when they are dealing with any type of serious illness in order to ensure that the patient’s goals, values, and quality of life are prioritized regardless of the circumstances of their health. This growing field of medicine is one that is often confusing to many both outside and even within the medical field, and this presentation will seek to demystify the field and highlight the incredible value we bring to any person going through serious illness.

About Dr. Alan Chiu

Dr. Alan Chiu is a board-certified physician in both Internal Medicine and Palliative Medicine and is an Assistant Professor at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center. After completing his residency training at University of Maryland Medical Center in Baltimore, MD, he practiced Internal Medicine and grew increasingly sympathetic to the unique and frustrating challenges faced by the patients and families dealing with serious illness. He completed Palliative Medicine fellowship training at University of California San Diego. He went on to work with the Sharp HealthCare system in the San Diego area as the Inpatient Medical Director of Palliative Care at one of their campuses. He joined as faculty at UT Southwestern in 2020 to continue his passion of training future physicians in effective and compassionate communication skills, particularly in the setting of serious and complicated illnesses, as well as understanding and addressing healthcare disparities present within the larger medical system. He specializes in Internal Medicine and Palliative Care, with additional expertise in symptom management, communication techniques, prognostication, advance care planning, and navigating patients and families through difficult decision-making.

Dr. Alan Chiu is a board-certified physician in both Internal Medicine and Palliative Medicine and is an Assistant Professor at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center. After completing his residency training at University of Maryland Medical Center in Baltimore, MD, he practiced Internal Medicine and grew increasingly sympathetic to the unique and frustrating challenges faced by the patients and families dealing with serious illness. He completed Palliative Medicine fellowship training at University of California San Diego. He went on to work with the Sharp HealthCare system in the San Diego area as the Inpatient Medical Director of Palliative Care at one of their campuses. He joined as faculty at UT Southwestern in 2020 to continue his passion of training future physicians in effective and compassionate communication skills, particularly in the setting of serious and complicated illnesses, as well as understanding and addressing healthcare disparities present within the larger medical system. He specializes in Internal Medicine and Palliative Care, with additional expertise in symptom management, communication techniques, prognostication, advance care planning, and navigating patients and families through difficult decision-making.

™

™