In this talk, Catherine breaks down the science of thought and shows how our mindset—or thought pattern—exerts a substantial influence on physical health. Most importantly, this talk gives specific strategies we can all use, no matter our natural tendency, to make minor tweaks in our thoughts and behaviors that will improve the quality and length of our lives.

C3 hosts a periodic C&C event series to share ideas among professionals. We truly enjoyed hosting Catherine and learning better ways to provide continuity of service to our clients.

Request an invite to a future event by emailing Rebecca Bates at rbates@c3fp.com.

Download her presentation and watch the full event recording below or at the top of the page!

Todd: The topic this morning is “The Art of Aging: A Prescription for Mind and Body.” For those of us who are aging, or know people who are, we will be concerned about it.

We are really pleased to have Catherine Sanderson on the call today. She is joining us from Amherst College. She’s a professor and Chair of Psychology in that department.

I first heard Catherine a few months ago when she did a radio program, and I had the honor of calling in and talking to her. That started our relationship and some great dialogue since.

She has many degrees in psychology from Stanford and Princeton University. She’s published articles, books, textbooks, and trade books. She joins us today to do a breakdown of the Science of Thought and show how our mindset exerts a substantial influence on our physical health.

We can’t separate the mind from the body. And more importantly, rather than just pointing out the issues, Catherine is also going to give us some specific strategies that we can use to help deal with those issues – no matter what our natural tendency may be. And she will show how we can make minor tweaks to our thoughts and behaviors that will improve the quality and length of our lives. We’ll take questions at the end, so please go to the Q&A section at the bottom of the screen and type in your questions.

Catherine, with that we’ll turn it over to you and we’ll go into hiding.

Catherine: Thank you very much for that lovely introduction. I’m so excited to be here and to speak with you all. I want to start by telling a story. The story is about my great-grandmother who spent her entire life living in the South. She was born in Louisiana; she spent her adult life in Mississippi and Louisiana. She grew up in a life of poverty. She lived in a mobile home pretty much throughout her life. She was living in a state in which there was not great education.

There were also not great opportunities for women. She was born in 1898, during a time in which women typically didn’t go to school or certainly didn’t attend higher education of any sort. Again, she was living in a life of poverty – in a state without great healthcare, and yet she lived to be 98!

When I think about her life experience and the kinds of things that allowed her to live a happy, healthy, and long life despite growing up in pretty dire circumstances in lots of different respects, what we now know from the field of psychology is pretty much the secret to her success. I’m going to be sharing some findings today from the field of psychology that look at what we know about the art of aging. In particular, what we know about the psychology of aging well. As well as the role that we can all play in controlling things about our lives in ways that in fact lead us to live happier, healthier, and longer lives.

I want to start with a poll. In particular, I want to ask you this question: ‘Have you ever heard the stereotype that older people are feeble and absentminded?’ I’m launching the poll and giving you a chance to share your response here. I’m going to stop talking for a second, and give people a chance to respond to this. One of the key findings from the field of psychology is that the stereotypes that we hold about aging, can in fact, exert a pretty strong influence.

So 62% of people have already participated, which is great. I’m going to give it another 10 seconds or so. If you want to get your vote in, I will reveal the responses. Alright, and now we’re up to 93%, which is great. So, I’m going to count down from five seconds and I’m gonna end the poll.

5…4…3…2…1…As you can see here, this is something! Eighty-seven percent of people – so most people listening today – have heard this stereotype. That’s just a really simple example of how we often hold (particularly within the United States) these negative stereotypes about aging.

I want to start by talking about the role of mindset. What we know, again and again, within the field of psychology is that mindset really matters. When we think about mindset in psychology it describes the thoughts that we have. This could be thoughts about ourselves, it could be thoughts about people around us, but overwhelmingly we know that mindset exerts a tremendously strong influence on our happiness on our health.

I’ll give you a few examples of how mindset plays out. More expensive wines have been shown to taste better in some really clever studies examining the power of perception. Researchers brought people in and they were given wine to taste. In some cases, people are told, ‘Wow, you know, this is a wine that is really expensive! It costs around forty dollars a bottle.’ In other cases, people have been told that the exact same wine – again, they’re all drinking the exact same wine – is a really cheap wine, ‘This costs four dollars a bottle.’

In these studies, everybody’s given the exact same wine to taste, and yet, what they find is that being told that the wine costs $40 a bottle, leads it to (seemingly) taste that much better than if they’re told that it costs $4 a bottle. That’s a powerful example about mindset.

We have an assumption in our society – it’s often true, but not always – that more expensive things are better or higher in quality. So, again, that’s why we have this belief that more expensive wines in fact taste better.

Another example: the stereotype that some people are naturally good at math. That is a very common belief in our society that math is genetically determined, that some people are sort of innately good at math and other people are not. The challenge about having that kind of mindset is that as soon as you believe that some people are good at math and that you’re not one of them. So guess what? You stop doing math.

You stop doing math because, after all, why should you try hard math if you’re not going to be good at it? The challenge of that stereotype in particular is that it can actually create a self-fulfilling prophecy. You believe that some people are good at math, that you’re not one of them, and so you reduce your effort in math. Lo and behold, that creates not being very good at math. That’s an example. Unfortunately, in this case, it can create stereotypes that have really negative consequences.

One of the common stereotypes, again within the United States, is that boys are naturally good at math and that girls are often not naturally good at math. About 15 years ago, a new Barbie was released on the market. I say it was about 15 years ago to illustrate that this was not 40 or 50 years ago. This Barbie had a remarkable feature. This Barbie could talk, she had four different expressions that she could say. You pull a little string, she would say one of them. So, Barbie’s release: she comes on the market, she says four different things, and one of them was this: ‘Math is hard.’

As soon as this Barbie was released, people were horrified. Parents, many, many parents expressed, ‘How could you possibly have a Barbie say ‘Math is hard.’’ The outpouring of concern actually led this Barbie to be pulled from the market immediately because people realized, ‘Oh wait, maybe that’s not a really great thing to be marketing a toy for little girls that feeds into the stereotype about math being hard for girls.’

But, here’s what struck me as the mom of the daughter and as a psychologist, many people had known about this production. Presumably focus groups and teams of people met and decided ‘Okay, this is one of the good things she would say.’ It did not occur to anyone in these meetings, and no one vocalized, ‘Maybe this is a problem?’

This is exactly how stereotypes create a mindset, and it gets reinforced, with really problematic outcomes.

For the scope of today’s talk, I’m going to discuss our mindset regarding aging. Because what the research shows, time and time again, is that when we have stereotypes, such as ‘Older people are feeble and absent-minded,’ which again was my poll question that 87% of people reported having heard that stereotype, that as soon as you have that stereotype, it creates a negative self-fulfilling prophecy. This means that it influences how we think about ourselves and how we think about the world.

This point was brought home to me about 15 years ago. I was heading to give a talk in New Jersey. I live in Massachusetts and the talk in New Jersey was about a four-hour drive from my home. The talk was on a Friday morning at 9 am. I had a very busy Thursday; I had taught, I had meetings, I’d gone home, and sort of frantically did laundry and had dinner with my family. Finally, at around 9 pm, I got in my car. Now, 9 pm was later than I should have left. I should have left earlier, but because I was leaving at 9, I just decided I would wear sweatpants and a ratty t-shirt to do the drive because I was just going to go and crash in my hotel room, and therefore, I was just going to wear what I was going to sleep in.

I get in the car at 9 pm, and at around 11 pm, my phone rings. My husband is on the line and he says, ‘Do you know that your suitcase is on the bed?’ No, I did not know that my suitcase was on the bed. I’m mindful that I can’t really give my talk in sweatpants and a ratty t-shirt at 9 am the next morning, so I said to him, ‘Could you please call and figure out what is open in Princeton before 9 am because I have to buy something.’ And he says, ‘Yes, I’ll get right on that, but I’ll call you right back.’

He calls back in about 10 minutes, and, as you can probably guess, there are not a lot of options. There’s one option and that is Walmart. I got to the hotel around 1 am. I got a wake-up call at 7 am and I drove to Walmart wearing my sweatpants and a ratty t-shirt, where I bought a complete outfit from the Miley Cyrus collection. It’s not what I’m wearing today. I buy this outfit, I give my talk, and at lunch, I confess to all the people sitting at my table what a horrible day I’ve had. You know, I’m wearing this outfit that I bought at Walmart at 7 am and everybody at the table thought it was hysterical. Ha-ha-ha, you know, absent-minded professor.

I tell that story because it actually is a powerful demonstration of how mindset matters. When that story happened, I was about 40. So, again, it was very funny: the absent-minded professor forgot her suitcase. If I had been 65 or 70, what would people have said? ‘Oh yeah, dementia, she’s losing her mind, you know, senior moment.’ That’s an example of how the stereotypes that we have regarding aging can reinforce and reinterpret very normal life behaviors.

I’m a college professor. Pretty much every week in my office, students leave stuff there. They leave cell phones, they leave apples, they leave wallets, they leave IDs, they leave umbrellas. I never think ‘Dementia, a senior moment, is setting in.’ That’s an example of how the stereotypes that we have about aging can actually lead us to interpret very normal behavior in line with these negative stereotypes and that can have really negative consequences.

One of the strongest and most consistent findings in the field of psychology and health psychology, in particular, is that mindset exerts a tremendous amount of influence on our health. This is true in a variety of different kinds of studies that have examined this broad impact of our thoughts on how we interpret various health outcomes.

We know that mindset influences health – you already know this – in very clear ways. The placebo effect, for example, illustrates very profoundly that mindset influences the experience of pain. You might remember a time in which you’ve had a headache or a stomach ache, and you’ve sat in a drugstore, a CVS or a Walgreens, and you’ve thought ‘Oh, what should I buy? Should I buy the more expensive pain medication, the name brand, pricier option? Or should I go for the cheaper, generic brand?’

This is a classic example, because you have a choice. You can buy the more expensive brand or you can buy the cheaper brand. This, however, is exactly what I described earlier about the effect of $40 wine versus $4 wine in terms of your perception. This is what research has shown very clearly – believing that something is more expensive leads it to work better. So, does this mean that the more expensive, name-brand products actually work better to relieve our headaches? Yes, yes they do, but they do precisely because they are more expensive. Name brand products tend to lead to better pain relief only because of the perception of their price.

Fascinating research has shown that if you bring in people and say ‘We’re going to expose you to a small amount of pain on your wrist.’ Often in psychology studies, this is a mild electric shock, or intense heat. The researchers say ‘Before I apply the heat, or before I apply the electric shock, I’m going to give you some pain-relieving medication, some lotion.’ Now, in all of these cases, it’s just regular lotion, it’s not actually pain-reducing, but what they have varied in these studies is how much you think the pain-reducing cream costs.

In some cases, they say ‘This is a very special cream, it’s $30 a dose.’ In other cases, they say, ‘This is a very special cream, but it’s been dramatically reduced, and it’s only 10 cents a dose.’ You’re told it’s a very special cream, but in some cases, you’re told it’s very expensive, and in some cases, you’re told it’s very cheap.

What they found is people who’ve had the cheap dose applied to their wrist report experiencing substantially more pain than people who believe they’ve received the very expensive $30-a-dose pain-relieving medication. This is another powerful example about mindset: when things cost more, we assume they must be better.

We also know that mindset influences sickness. They’ve done fascinating studies; a lot of this research has been done at Carnegie Mellon University in the Medical Center. They have recruited healthy volunteers. They measure their level of mindset, particularly about positivity. So, are you more optimistic, you know, positive thinking, or are you more negative and pessimistic in your thoughts?

Then, after you have experienced this measurement of your positivity versus negativity, the researchers inject a cold virus up your nostril. The researchers then do something fascinating. They measure whether you develop signs of the cold over the next four weeks. Every day, they collect saliva samples to see if you are manifesting antibodies to the cold in your body. Every day, they ask people to complete symptom reports: Are you coughing, sneezing, runny nose, sore throat? And, my students’ favorite: Every day, they gather the people’s used tissues and they weigh them to measure mucus production! Here’s what’s fascinating, people who have a positive mindset – again, high levels of optimism – show a lower likelihood of ever manifesting signs of the cold. No matter how they measure it! This is suggesting that a positive mindset actually leads you to not develop a cold even when it has been directly inserted into their body. A powerful example of the power of mindset.

In one of the most profound illustrations, researchers have also examined the placebo effect applied to surgery. What they’ve done in these studies – and the most famous one was done in Houston at a Veterans Administration – researchers brought in men who were all veterans, who were complaining of knee pain. They randomly assigned them to one of three conditions. Men in one condition actually had routine arthroscopic knee surgery. In another condition, the surgeon cut the knee open, scraped the cartilage, sewed the knee back up. In the third condition, the surgeon cut the knee open and sewed it back up, so literally, all they did was create a scar.

Then, the researchers examined rates of recovery for men in all three of those conditions for the next 18 months. Every month, they surveyed them and asked, ‘How much pain are you in?’ They ask about mobility: ‘How is it climbing stairs? How’s your flexibility? How are you feeling?’

Here’s what they found: nothing. What they found was nothing! Men in all three of these conditions improved at an equivalent rate. This is a profoundly important finding because what it suggests is that even for men who didn’t have the actual arthroscopic knee surgery, they also reported improvement in terms of lower pain, better mobility, better flexibility, and so on.

This does not mean that surgery is all fake and that surgery is all in your mind, that nobody should have surgery, etc. What this study points to is the power of mindset. If you’ve been experiencing some pain, and it isn’t going well, and all of a sudden, you now have this opportunity to feel better and you believe that a surgical procedure has been done, so surely you’re going to feel better, that all of a sudden it may lead you to change your behavior in other ways. Perhaps you follow your physical therapy recommendations, and that leads to better mobility and less pain. Maybe you decide, ‘Well, now I’ve had surgery, I’m going to feel better.’ So, you exercise a little bit more, or maybe lose some weight, or change your diet in some way. The key is: mindset may influence our behavior in a variety of ways that in fact help us recover from surgery.

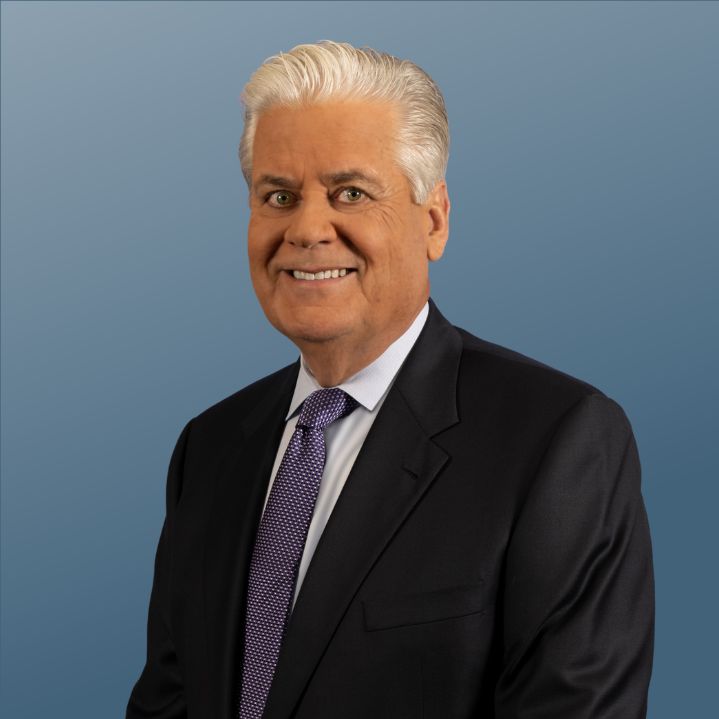

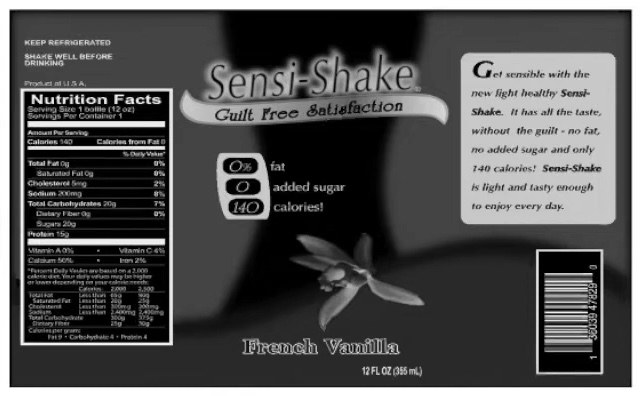

Some fascinating research coming out of Stanford University also points to an important way in which mindset may actually change physiological responses in our bodies in ways that may change our response to a variety of different circumstances. In one very fascinating study, researchers brought in people and had them drink a milkshake. In all cases, it was the exact same milkshake, but they told people very different things about that milkshake. I’m going to show you the specific label that was on the shake for people in one of two different conditions.

People in one condition came in and they were told, ‘You are drinking a really rich, decadent, dessert-type milkshake,’ and as you can see on this label, they were told this is a wonderfully delicious shake. It’s french vanilla, it’s high in calories, it’s high in fat, and again, this is a dessert-type drink. It is called Indulgence.

People in the other condition were given the exact same drink, but they were told something very different. They were told this shake is a diet drink. The name is Sensi-Shake. It’s zero-fat, zero added sugar and only 140 calories. Again, it’s a very low-fat diet type of drink.

In all cases, people are drinking the same thing. So, if your body is just responding to what you took in, what you consumed, you would anticipate that hormone levels are exactly the same in both conditions. But, that’s not what they found.

The researchers in this study were particularly interested in measuring a hormone called ghrelin. Ghrelin is often described as the hunger hormone; it basically tells your body when you need to eat. Higher levels of ghrelin say ‘Eat, eat you’re hungry,’ while lower levels of ghrelin say ‘Yes, I’m full, I’m good.’

Here’s what’s fascinating: people who had the drink that they believed was a diet drink showed increased levels of ghrelin. Their mind believes that they’ve just consumed a diet drink, so surely, they must be hungry. They’ve had no fat, no sugar, and only 140 calories. So, ghrelin levels for these people rose, telling the people, ‘You need to eat, you are hungry.’

People who believed they have the exact same drink but that it was a rich, fatty, high-calorie drink, showed low levels of ghrelin. Their body believed – again, because their mind believed – ‘I’m full.’ That’s a really fascinating example of how mindset doesn’t just change how we feel. Mindset actually can lead to physiological changes in the body that profoundly influence, in this case, feelings of hunger.

In another fascinating study about the power of mindset – this is one of my favorites – researchers actually did this study with women who had jobs cleaning hotel rooms. They took women who worked for one particular hotel chain and divided them at random into one of two groups of women. In one group, they were told ‘the Center for Disease Control and Prevention has demonstrated that it’s extraordinarily important to engage in regular kinds of physical activity and that engaging in regular, physical activity is an extraordinarily important part of good health. So, you really need to engage in regular physical activity for at least three to five times a week at least 75 minutes of time. This is an important part of health.’

Researchers then told women in the other group the exact same information about the importance of engaging in regular activity, ‘This is an important part of health,’ and so on, but, they also added one more key set of findings. They told these women, ‘Hey, and by the way, cleaning hotel rooms counts towards your allotted exercise, so if you are cleaning bathrooms, vacuuming, changing sheets, etc, all of that counts as part of your weekly physical activity allotment.’ All the women were told they need to exercise, but some of the women were told, ‘By the way, your job cleaning hotel rooms actually counts.’

The researchers then went back to all of the women in the study four weeks later. Four weeks after they had told them this information, they measured weight, body fat, and blood pressure. Here is what is fascinating: the women who had been told, ‘Oh, by the way, your cleaning hotel rooms count as your exercise,’ had lost weight, had lower levels of body fat, and had lower blood pressure.

That is a profoundly important finding. What it’s telling us is that, in fact, just believing that the exercise you are doing as part of your job is beneficial and counts towards your exercise allotment led to lower weight loss, lower body fat, and also lower blood pressure, which is, again, all a really, really fascinating finding.

Todd: I have a quick thought. The examples you used are very well outlined in your book, which is a terrific book, but my question is – and we’ve talked about this briefly – when I was studying for my master’s degree in social work and we studied ageism, it was a term that was just being coined. The difference to me – and what these exercises are – these are external influences on the individuals, whereas, with ageism, we internalize what we think it’s going to be like when we’re older. I don’t know what your 40-year-old self told you when you were going to New Jersey, but the idea of internalizing these stereotypes and then when you get to that point, ‘I left my luggage, what do you expect, I’m older.’ Can you touch on that and the impact of that as you’re going through these other points?

Catherine: Yes, wonderful question, and really, a super important question. Because, here’s the key: ageism is a type of mindset. Ageism is a mindset, and as you said, it’s a type of mindset that is culturally determined, because, in certain cultures, we expect that aging is full of wisdom, life experience, and greater knowledge. That’s really what’s key about ageism is it’s very much a socially, culturally determined externality. Wonderful point.

Exactly in line with what Todd just said, what we know is that our mindset about health matters. Our mindset about health can influence our hormone levels, and can influence changes in our body, and one of the most profound examples is that mindset also influences aging in a variety of different ways.

Let me turn to some of this fascinating research. In one study, they brought in older adults and actually gave them an article to read. Some of the people got an article that really described the aging process as being negative in terms of memory. “With age, there is a natural decay in the neurons in the brain that makes memories harder to come by.” Other people received an article that was about memory and aging that was very positive. “With aging, people have experienced more life events and that actually helps them to better retain information because they have these different experiences and that makes them able to organize and add new information in a very effective, functional, and efficient way.”

So, you read one of these two scientific articles, and then, they had people – and again, this was all older adults, 55 and older – complete a memory task. Here’s what they found: If you’ve just read an article that suggests memory goes naturally with age, it gets worse. People, in fact, showed poor performance on the memory task. Again, cueing people with a positive versus negative stereotype about mindset about aging, led to lower performance in terms of memory tasks.

Researchers also showed that, again, walking speed can change based on your stereotypes about aging. This study was done with college students, but again it profoundly illustrates that just even reminding people about the stereotypes about aging can lead to negative outcomes.

They brought college students in. The students completed a task on a computer, and what they did while students were completing this task is the researcher splashed up words at a subliminal level. The key here is that this is below the level of consciousness. They flashed up words – again, at an unconscious level. Some of the words for people were neutral words for people in one condition.

People in the other condition saw words that cued stereotypes about aging, arthritis, shuffleboard, early-bird dinner, gray hair, wrinkles, etc. When the study was over, the researchers said ‘Thank you so much for coming in, here’s your five dollars,’ but the key is this next part is what the researchers actually were measuring. The second the student walked out of the room, the researcher pressed a stopwatch. They timed how long it took students to walk down the hall to the elevator at the end of the hall.

Here’s what they found: Students who had been cued with stereotypes about aging, actually walked slower to the elevator! That’s again, a reminder about how our mindset – even at a subliminal level – about the cues of aging can lead to slower walking speed.

Research also shows that holding negative stereotypes about aging also predicts cardiovascular problems. In this study, they brought in adults – ages 55 and older – and they had them rate their stereotypes about aging: ‘Do you believe that aging is going to lead to deficits?’ Again, stereotypes about aging are negative. Or, ‘Do you have positive expectations about the aging process?’

So, they looked at people’s positive versus negative stereotypes, and then they examined people over the next seven years to see how many people developed different kinds of cardiovascular problems: stroke, heart attack, congestive heart failure. All of this research was also controlled for other factors statistically. Things like ‘Did you smoke?’ or ‘Did you have high blood pressure?,’ ‘What was your family history?’.

Here’s the data: People who have positive stereotypes about aging were half as likely to show cardiovascular problems as people who had negative stereotypes about aging. This finding illustrates the power of ageism. If you have negative stereotypes about aging, which we often see in our society, overwhelmingly you are twice as likely to experience cardiovascular problems. Even controlling for other factors biologically that we know predict cardiovascular problems. Most importantly and in the saddest kind of way, we also know that the same kind of influence on negative stereotypes about aging impacts longevity.

In this study, they asked adults ages 50 and older to complete measures of stereotypes about aging. You had to rate your agreement with: ‘Things keep getting worse as I get older,’ or ‘As you get older, you get less useful.’ Then, after people had recorded their responses to these questions, they followed these people for 23 years to look at the duration of how much they bought into these negative aging stereotypes.

Here’s what they found: Adults with positive stereotypes lived on average seven and a half years longer than people with negative stereotypes. This is a profound illustration – responding to Todd’s question about the power of having negative stereotypes – about aging actually leading people to live less long. This, of course, is the most profoundly important finding.

I want to turn now to my second poll question. I want you to think about the different examples that I have shared today from the research. Which of the findings do you find most surprising or intriguing? Is it telling someone their drink is high in calories reduces feelings of hunger? Is it that undergoing placebo surgery can lead to less pain? Is it telling someone their work counts as exercise leads to lower blood pressure? Is priming someone with cues of old age leads to slower walking? Or is it that holding positive stereotypes about aging predicts living longer? I’m going to give you a minute to report what you think, and I will show you the different responses.

Alright, I’ve had half of the people already responded, which is great. Now it’s 75 percent of people. So, I’m going to give it – in the interest of time – maybe 10 more seconds. What’s interesting is I’ve had votes already for all of the different responses. I’m going to give you five more seconds from now. 85 participants is great. So, I’m going to count down from five and then I am going to stop the poll and share the responses.

5…4…3…2…1. I’m going to show the results. The thing that was most surprising for people here – nearly half of you – is undergoing placebo surgery can lead to less pain. I will say, when I give this talk (pre-COVID) in a big hotel ballroom, this is the research that the attendees believe is scary. Again, let me be clear, it doesn’t mean that all surgery is fake. That was the most common response.

I now want to move on because I really want to talk about the ‘why’, because you’re probably very interested. I’ve just shown this data about the link between having positive stereotypes about aging, and you actually live seven and a half years longer. The really important question, of course, for all of us is ‘why?’. How does mindset influence longevity? I’m not going to give you a definitive answer today, but I’m glad to talk more about these findings. Also, of course, in the Q&A.

Briefly, there are three distinct sorts of theories that people have about how mindset impacts longevity in particular. One theory is that your mindset is basically giving you a greater sense of personal control. That is one of the keys: when we know that there are things that we can do that are within our own control, it actually makes us feel better. There’s lots of research in psychology and this, in all honesty, feels particularly timely right now about the hazards of uncertainty that when we feel a lack of control over our environment, it actually can make us feel worse. It can make us feel more stressed, and so, having a sense of ‘Okay, there are things that I can do to age well’ actually gives us lower levels of stress because we have a sense of personal control.

One of the earliest demonstrations about the power of control is a fascinating study. It was done a number of years ago in the early 1970s. The researchers took people who were living in a nursing home and assigned them to one of two very similar conditions to try to improve life in the nursing home. People in one condition were told ‘We’re going to try to improve life in this nursing home by giving you additional benefits.’ They provided these people in the nursing home with a bunch of added pluses. They were given plants and said ‘We’re going to put a plant in your room, and don’t worry, the nurse is going to take care of it, but it will be there. Also, we’re going to start doing game nights, and game nights are going to be in this one specific night. Here are the different games we’re going to play. We’re going to offer movie nights, and here are the different movies we’re going to show. They’re going to be held on this night, and we hope you’ll come.’ So, for people in this condition, they got a plant, they got a game night, they got a movie night – all positive things.

Now, here’s the little switch: People in the other condition were given similar things but in a different way. They were told ‘We have a bunch of plants, and if you want a plant, they’re at the nurse’s station. Come and choose your plant and take the plant you want. And also, you have to take care of it yourself.’ They were also told ‘We’re going to do a game night, and what games do you like? Please rate which games you want to see. Also, what night do you want to see them?’ They were told ‘We’re going to do movie nights, which movies do you like? Which movies do you want to see? Also, which nights do you want to see them?’

As you can probably tell from my description. In all of these cases, people were given something beneficial. They were given plants and movies and games, but what they varied was the level of control that they had. For some people, they had lots of control: which night, which games, which movies, which plants. For other people, those things were foisted upon them. The researchers then went back to this exact same nursing home 18 months later and what they examined was who is still alive now. The overall death rate in this nursing home over an 18-month period was 25%. Twenty five percent of people in general in this nursing home had died 18 months after. Then, they compared that rate for people who’d been under one of these two conditions. What they found was, for people who’d been told ‘Here’s your plant, here’s your movies, here’s your game night,’ 30% of those people had died. Statistically, that’s no different than the 25%. It doesn’t mean that giving people these things led them to die more, but it was 25% overall and 30% of the people who were in that group were given additional things.

However, for people who were told ‘Do you want a plant, and which ones, and which movie night, and which games,’ and so on. For this group, only 15% had died. What that study tells us is that giving people a sense of control actually led to a significantly lower likelihood of dying in the next 18 months. Fifteen percent versus 30%. This is one of the first studies that came out suggesting that we really need to provide opportunities for people to exercise control, especially if they are in a low-control setting, such as a nursing home. Having a sense of control, something that you can do, that you can exercise some choice in your environment, is a really important predictor of longevity.

Another factor is, perhaps people who have a positive mindset about aging adopt better health habits. ‘I’m going to live longer, so I may as well take care of my health,’ and that’s going to really matter. Perhaps, people start exercising or stop smoking or something. Maybe having this positive mindset about the aging process actually leads people to adopt better health habits: seeing the doctor, and adhering to medical recommendations.

Finally, and I think probably most importantly, believing that you have a positive outcome and positive expectations about aging may lead to a lower physiological response to stress. You don’t have to worry about the aging process because again, you have control over that process and that leads to benefits in terms of the level of cortisol in the brain, a particular hormone that’s in processes of stress. Also it leads to lower cardiovascular reactivity, blood pressure, heart rate, etc. Perhaps adopting a positive mindset regarding aging leads us to have all of these benefits: a greater sense of personal control, better health habits, and a lower physiological reaction to stress.

Carolyn: As I was reflecting on what you were sharing, I thought about an experience I had a couple of weeks ago. I was traveling for business. While sitting in the airport, guess what happened? The flight got delayed [laughter]. I am sure you have experienced it. Oh my goodness, there was a lot of immediate chatter. We were all sitting there with our masks on (muffled chatter is a little different). I had been reading your book, and it was interesting to see how some people received that news. They immediately became so anxious and stressed. Then, others were just like, ‘Okay, let me see what I can do.’ I find myself easily tending towards those who were getting very excited. Then I thought, I was going to go to my room and read. I can sit here and read. So, once it dawned on me that I had the same hours in the day – and you talk about it often – that reframing gives you back control. I wonder if you’d share more about that.

Catherine: That’s such an important point. By the way, good for you to practice! I love that example. It is such a simple example about the power of our mindset. I’m in this airport, I wish I wasn’t here, now there’s this delay,’ etc. It would be very easy in that mindset to get into, ‘Oh, this is so terrible, and I’m going to get home later, and now, I’m not going to do whatever,’ and to be able to say at that moment, ‘I’m going to take out my book, sit here, and read. I’m going to go get a cup of coffee, whatever.’ That’s a really powerful example of the power that we have to shift our mindset. What’s so important about that example that you just shared, Carolyn, is that it’s something completely within your control. It’s something that doesn’t require you to be the pilot or you to be the fixer or something. It’s something within our control, and that’s what I love about the field of positive psychology. Learning these tools and strategies are things that we can call up and respond to in the moment. There’s so much in life that we can’t control, and your example just now of taking something, admittedly, that could be a stressful experience and being able to say, ‘Let me take out my book, I’m gonna sit here and read’ is such a powerful example. Thank you so much for sharing.

Carolyn: Thanks for adding.

Catherine: As Carolyn’s example illustrates, that is the epitome of how simple some of these strategies are that can change our mindset. As Todd described earlier, the mindset about ageism is something that we can control in the same way and lead to substantially important benefits for us all.

Let me give you a few other strategies that we can adopt in our own lives. I’m hoping that I have one that speaks to each of you in some way.

One: Change your stereotypes. As Todd described earlier, the power of ageism is so strong in our society that we often hear negative examples about ageism. Instead, change your stereotypes. This is one of my favorite stories about a woman in her early 90s who became the first ninety-year-old to successfully run the San Diego Rock and Roll Marathon. When we think about ageism, this is a powerful example of what happens with aging well. We can run a marathon! I’m 51; I have never run a marathon. It doesn’t seem likely that that’s going to happen, but now I know that I have a whole lot more years that I can train, because my stereotype about aging is ‘you can be a marathon runner’. When we talk about Clint Eastwood, he directed Oscar award-winning films – American Sniper, Sully – well, into his 80s. The power of being able to think creatively and to direct people in Oscar award-winning films. Many of us can think about RBG’s writing as very intelligent, informed and acute decisions on the Supreme Court well into her 80s. We can change our stereotypes about what comes with age.

Two: Exercise (anything counts). What’s so fabulous about this one is that anything counts. There are so many different ways that we can exercise to improve our happiness and our health. Research shows that people who engage in any different kind of exercise – could be in a group exercise class, walking, playing golf, meditating, or doing yoga – think about aging as beneficial for physical health. Exercise is also really important for healthy aging; it keeps us not just physically strong, it also keeps us mentally strong, and it elevates our mood. Exercising in all different ways is a tremendously important way to improve physical well-being, psychological well-being, and the aging process. It’s not one-size-fits-all. Choose the kind of exercise that resonates with you and your experience.

Three: Meditate. This is one of my favorites because it’s so simple. Meditation is cheap. It’s easy. You can do it alone a few times a day, or once a day. Powerful research suggests that the process of meditating actually changes parts of our brain, both our activity and the structure of our brain in ways that not just make us feel better in terms of happiness and health, but also lead us to be kinder. Research has shown that people who meditate regularly show changes in particular parts of the brain that connect with compassion and empathy for other people.

Four: Keep Learning. I’m a professor, I’m a nerd, and maybe I’m biased, but lots of research suggests that one of the keys is that you have to keep exercising your brain. Early in life, people are forced to learn. They sit in my college classroom, they sit in high school classrooms, they learn new things in their jobs, but learning can happen throughout the lifespan. People who keep learning and doing new things show tremendous improvements and advancements in terms of ability to retain and master new different kinds of information. That can be taking a class, it could be doing a crossword puzzle. I speak regularly for something called One Day University, which is a lecture series that brings professors to people in their Zoom environments all the time. One of the reasons that I love doing these kinds of talks is to help people keep learning across their lifespans.

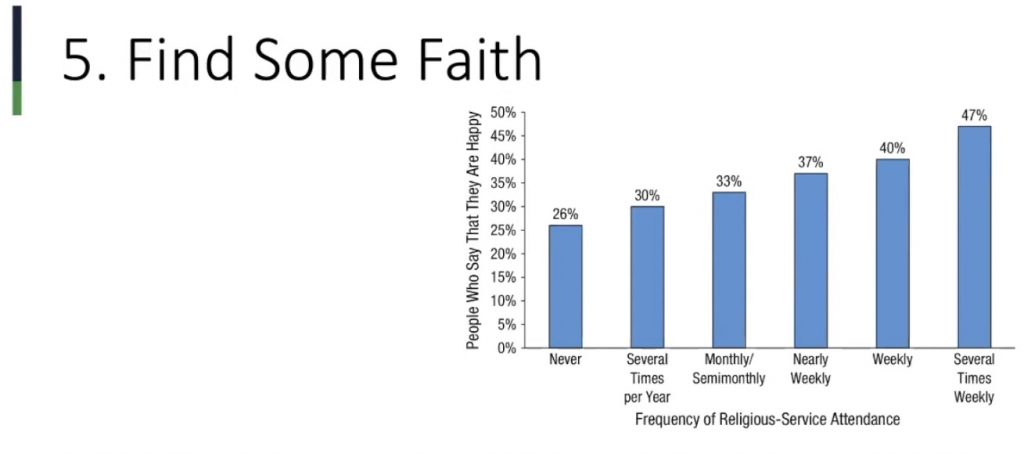

Five: Faith. Fascinating research has also demonstrated the profound importance of finding some faith. People who have religious beliefs and adopt religious practices show higher levels of happiness and also better health and even longevity. This research study examined the frequency of attending religious services in terms of rates of happiness. As you can see on this diagram [below], people who attend religious services weekly, or several times a week, actually report higher levels of happiness. That data is perfectly mirrored in terms of frequency of religious service and life expectancy. In the interest of time, I’m just going to hold this here, but there’s really interesting research examining the different mechanisms that explain these associations. Some people point towards religious beliefs that lead them to engage in better physical health. Some religious observations may be associated with things like not smoking or not drinking, etc. There’s also really interesting research suggesting that religious faith often gives us a positive mindset. Like ‘God won’t give me more than I can handle’ or ‘If I pray, somebody is listening.’ Perhaps most importantly, religious beliefs often give us connections. I’m going to talk about this momentarily. You can see in the data on attending religious services. Attending religious services may actually give us access to a social network of other people who support us and care about us. It really may be about the social support that is really the benefits of adopting religious beliefs.

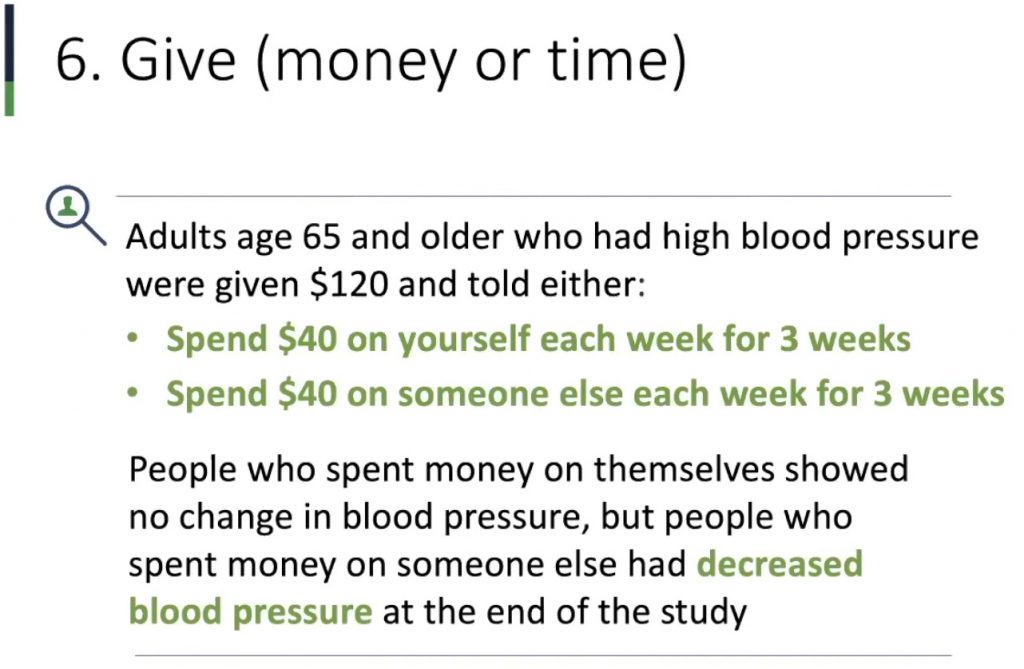

Six: Giving matters. I have an entire chapter in my book about this because giving is one of the most profoundly important ways in which we experience better happiness and health. In one experimental study, they brought in adults ages 65 and older with high blood pressure. They gave them $120 in cash, but then they gave them instructions: either spend $40 on yourself each week for three weeks or spend $40 on someone else. Here’s what they found: people who spent money on themselves showed no changes in blood pressure, but people who spent money on someone else had lower levels of blood pressure at the end of the study. Giving to somebody else actually led people to be healthier. Giving matters: that could be money, could also be time, or volunteering in your community. A study in California found that people who volunteered for two or more organizations were 44% less likely to have died during the five-year follow-up period than people who did not volunteer. Giving is good for us in terms of health, in terms of survival.

Seven: Positivity. We know that focusing on positivity matters. Adopting a positive mindset – I talked about earlier – is associated with better health. Here is a fascinating study that was done with nuns. The researchers looked at nuns’ diaries and coded them for positivity or negativity. As you can see here, the top quote is from one nun and was very sort of factual: ‘I was born…my candidate year was spent here…I’m gonna do my best for our order,’ and so on. At the bottom example is from a nun who had a real focus on positivity. You can see here just in the quotes: ‘Bestowing upon me grace…it was a very happy one…eager joy,’ all of these sorts of positive emotions. So, they looked at the degree of positivity, and then they looked at how old these nuns were when they died. As you can see here, nuns who were in the highest quartiles in terms of happiness were much more likely to live to 90 to 95.

Eight: Get a Dog. Research has shown that having a pet is profoundly important in terms of longevity. Fascinating research suggests that just staring into your dog’s eyes leads to an increase in oxytocin, a hormone that’s actually the bonding hormone. So, it actually makes you feel good, and it’s not just spending time with dogs.

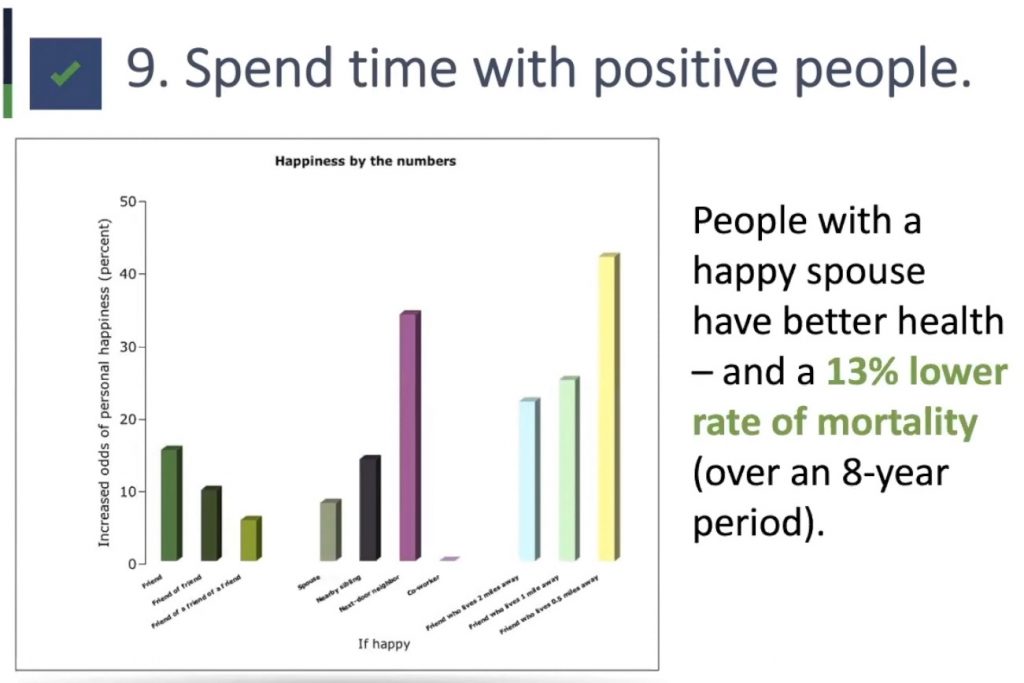

Nine: spend time with positive people. As you can see in this diagram, people who spend time with happy people – friends, spouses, neighbors, especially people that live nearby – experience higher levels of happiness themselves, suggesting that happiness is contagious. Research has also shown that people with a happy spouse actually have better health and are less likely to die over an eight-year period. Spending time with people, in general, is good, but positive people are especially good, and that brings me to my final point.

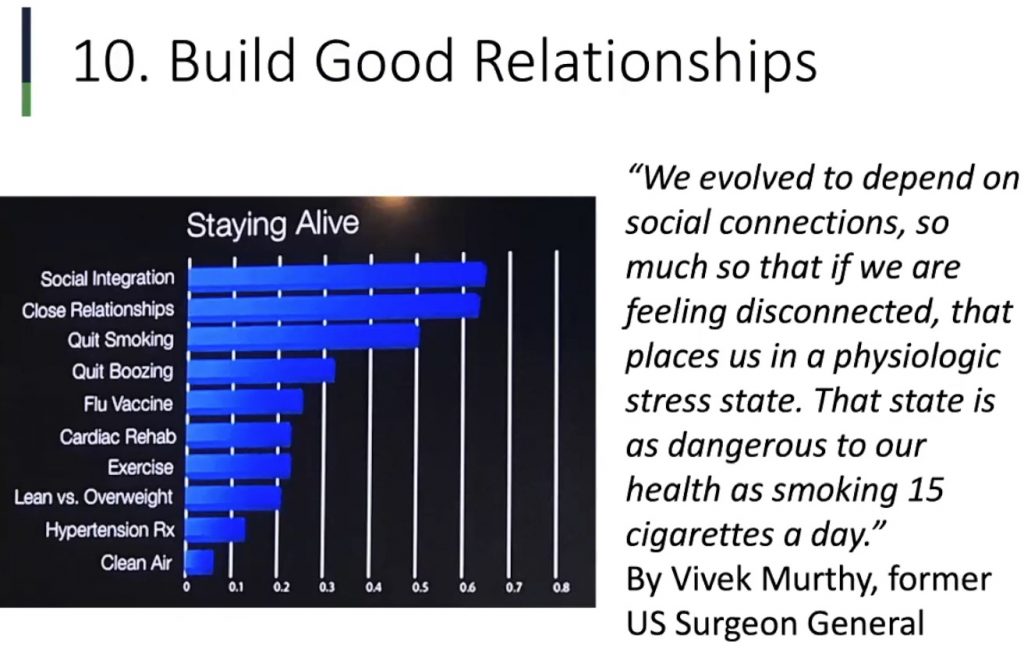

Ten: building good relationships. The single best predictor of our happiness as former U.S. Surgeon General Vivek Murthy says, ‘We evolved to depend on social connections, so much so that if we are feeling disconnected, that actually leads us to feel physiologically stressed. Just as dangerous as smoking 15 cigarettes a day.’

The chart below illustrates that in terms of the predictors of longevity, social integration, and close relationships are even stronger predictors of longevity than not smoking or not drinking, or having your flu vaccine.

I want to end with one final poll: Which one did you find most useful? I’m going to pop up that poll, but I want to end with a picture of me, my grandmother, my mother, and my great-grandmother to revert back to the example that I shared with you today. When I think about her life, she did many of these things that you’re seeing in your poll. She had very positive stereotypes about aging, despite where she lived, she was very religious, she had a very strong network of friends, she was always giving to people around her, and she really focused on building good relationships.

I’m gonna leave this poll up and let you respond. Then, I will share your responses. I’m so looking forward to any questions that we might have. I know we got to have a few of them earlier, which was great.

Todd: Catherine, I know that Celeste has read your book and has a question coming from the perspective of a Millennial. So, Celeste, please ask Catherine your question while the poll is being calculated.

Celeste: My question is, “How has social media and streaming, like Netflix, impacted healthy aging?’”

Catherine: Thank you so much for that really smart question, Celeste. What we know is that in many cases, social media can lead to a sense of comparison. You know, ‘How am I doing compared to other people around us?’ and we have this forced sense of comparison. In some cases, that can actually make people feel less happy. The key is what we are seeing on social media. Some people are seeing examples on social media of people aging successfully. That can lead to benefits. Other people find themselves doing comparisons that are less effective in that sense. I think one of the biggest challenges, and we see this research a lot with teenage girls, in particular, that when there’s a sense of, let’s portray aging as ‘I have to get rid of my wrinkles and rid of my gray hair and rid of these other things,’ it can make it seem that aging is not a time of feeling happier or healthier or more attractive. That can be particularly detrimental.

So, the big question here is who are the kinds of comparisons that you’re making, and are you comparing yourselves in ways that make you feel good or less good? Great question Celeste.

Let’s share the results. Number one: many people found exercising very beneficial. Building good relationships is also right up there. As is giving, and keep learning, that was another one that 47% of people submit. People benefited from all different examples.

Todd: Catherine, thank you very much! Very, very thought-provoking, I hope people have enjoyed your book. C3 has three more copies for the first three people who email us after this presentation. We’ll get you a copy of her book, and I think you’ll find a whole lot more that, obviously, she couldn’t cover in one hour.

We’re also pleased to announce that on February 22 of 2022, so that’s 2-22-22, Tom Rogerson, who many of you have heard before, will be sharing his thoughts. He and his wife, Cathy, run a practice dealing with family governance and helping healthy families and dealing with conflict.

So Tom, if you’re on, please jump in and give us 30 seconds of what you plan to cover in February.

Tom: Sure, thank you very much, Todd, and everyone here. I’m actually going to be doing a continuation of what you just heard from Catherine, but in relation to family. The presuppositions we have: the fears of parents when it comes to their children, of creating entitlement. We don’t want our family wealth and our family legacy to disappear quickly. We bring presuppositions to that and create a culture that actually creates the problem we’re worried about in our families. We’re going to talk about that and what it looks like and what you can do about it and how.

Hopefully, it can totally transform your estate plan for the benefit of your family to find your wealth as a blessing, and not the curse that so many families find it to be. That’s a thumbnail sketch of what we’re going to be talking about.

Todd: You all are in for a treat, just like you were today. Tom is a tremendous communicator. He and his wife have a very, very significant practice, and we are so looking forward to visiting with him.

Again, Catherine, thank you so much for your comments, and your input; and for all who joined us, we appreciate you taking the time. This will be recorded, so if you want to have somebody look at it, just let them know they can go to our website and take a look at it.

Thanks again, everyone! Stay safe, have a great afternoon.

Catherine: Take care.

Enjoying Catherine’s content? Check out her books here.

™

™