READ IN SPANISH

Financial Planning for Global Citizens

How life insurance can help global citizen clients manage their estate tax liability

Todd S. Healy

Global Citizens doing business in the United States are a growing clientele in the financial services industry. As the global economy continues to grow, and as wealth holders in foreign countries continue to find promising opportunities in the U.S., global citizens will require more knowledgeable advice on how to navigate the unique and sometimes complicated rules that govern their assets.

Most global citizens, however, are unaware of the tax liabilities that they are exposed to on account of their residency status in the U.S. As such, it is crucial that global citizens and their advisors carefully review their estates in order to uncover potential tax issues. More importantly, advisors should look early on for solutions to these issues in order to protect their clients’ assets.

Below, we discuss the intricate estate tax liabilities that global citizens are subject to, as well as strategies for managing them. Specifically, we will talk about how life insurance can be a valuable tool for maintaining liquidity while meeting U.S. tax requirements.

Residents vs. True Global Citizens

United States tax code makes two important distinctions when it comes to global citizens: Resident Aliens and Non-Resident Aliens (also referred to as True Global Citizens, or TGCs). The difference primarily comes down to how much time an individual spends in the country, though TGCs will typically also have fewer assets in the U.S. It’s an important distinction, however, because the two groups are subject to dramatically different tax liabilities (which we’ll discuss later in detail). Moreover, the Internal Revenue Service has its own set of requirements for residency apart from other legal requirements. In many cases, an individual might not even be aware that they are considered a resident for tax purposes, because for other legal matters they are not.

The IRS has two tests for whether an individual meets residency status for tax purposes. Those requirements are as follows:

The Green Card Test

If an individual has applied for and been granted an Alien Registration Card, known familiarly as a “green card,” they will be considered a resident. This requirement seems pretty straightforward, but it can offer surprises. For example, an individual might decide that they no longer want U.S. residency and choose to surrender their green card, thereby relinquishing American residency. There are multiple bureaus, however, that have to process this action; and if it’s improperly submitted, an individual might still be subject to resident requirements, even if they believe they have given up residency.

The Substantial Presence Test

Even if a global citizen does not hold a green card, they may still be subject to resident liability if they meet what the IRS calls the “substantial presence test.” The details of this test can become rather complicated, but essentially it states that if a global citizen spends a certain amount of days in the U.S. during a given period of time, they will automatically be considered a resident for tax purposes.

Because of the complicated nature of the substantial presence test—and because it goes into effect automatically, regardless of whether an individual meets other legal requirements for residency—many wealth holders might not even be aware that they’re subject to resident tax status. It’s important, then, to be clear on an individual’s residency status with the IRS and to plan accordingly.

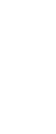

Tax Liabilities of Residents and TGCs

Why are these IRS distinctions so critical? Because, as we mentioned, residents and TGCs are subject to substantially different tax policies, which require different planning strategies. These policies most crucially apply to estate taxes, which assess such assets as real estate, valuables (such as jewelry, antiques, or artwork), stock shares, and certain bank deposits, among other things.

™

™